The generous donation from the late artist’s estate comprises an invaluable learning tool and a significant addition to the print research collection at the ECU Archives.

A new donation from the estate of artist Ann Kipling (Dip. Painting 1960) brings more than two dozen prints from across Ann’s career to the Archives at Emily Carr University of Art + Design (ECU).

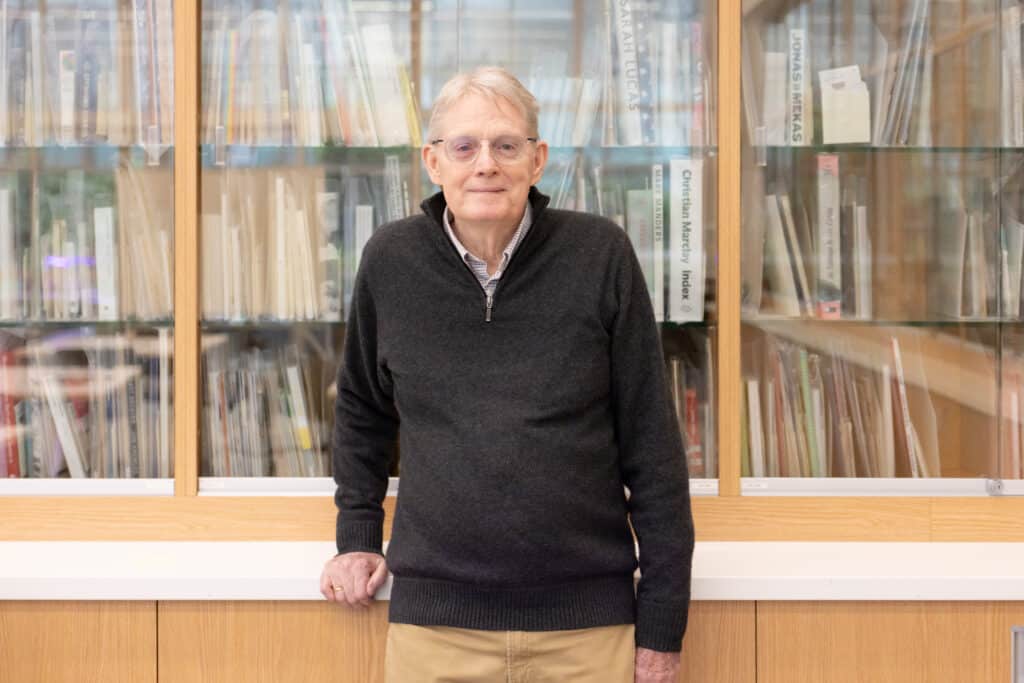

“It was an honour to be approached to care for Ann Kipling’s prints. Each one is beautiful but as a grouping they are an incredible resource for our community’s students and researchers,” says ECU archivist Kristy Waller, who, in collaboration with ECU faculty members Ana Diab and Beth Howe, recently completed a multiyear project to help support artists and student access ECU’s broader print collection.

“One of our findings was that the collection could be improved as a resource by having more women and local/ECU-connected artists represented. The Ann Kipling donation is an amazing beginning.”

The prints, which span four decades, provide a vital window onto Ann’s singular artistic oeuvre, says Ian Thom OOC, senior curator emeritus at the Vancouver Art Gallery (VAG). Ian, along with writer and curator Robin Laurence, is an executor of Ann’s estate.

“Ann’s practice is very distinct within this country; she had her own path, and she followed that path,” says Ian, who programmed Ann as one of more than 100 exhibitions he organized during his three decades at the VAG.

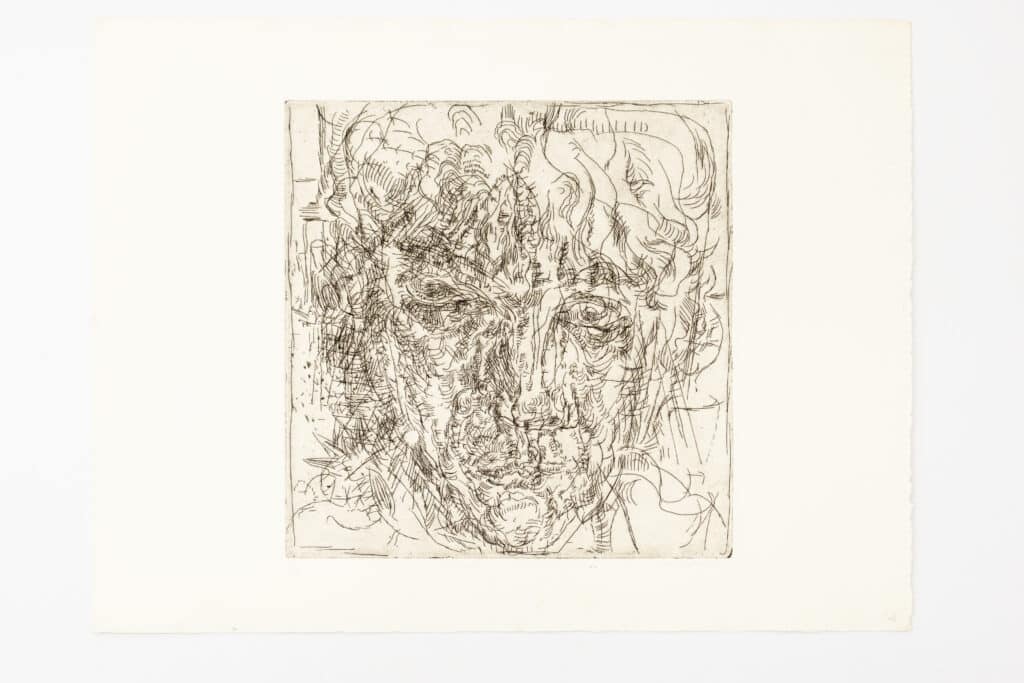

“She had an extraordinary degree of integrity. The most important thing for her was her work. She’s the kind of person who did 20 drawings on Christmas Day because the journey and the exploration were what truly mattered to her.”

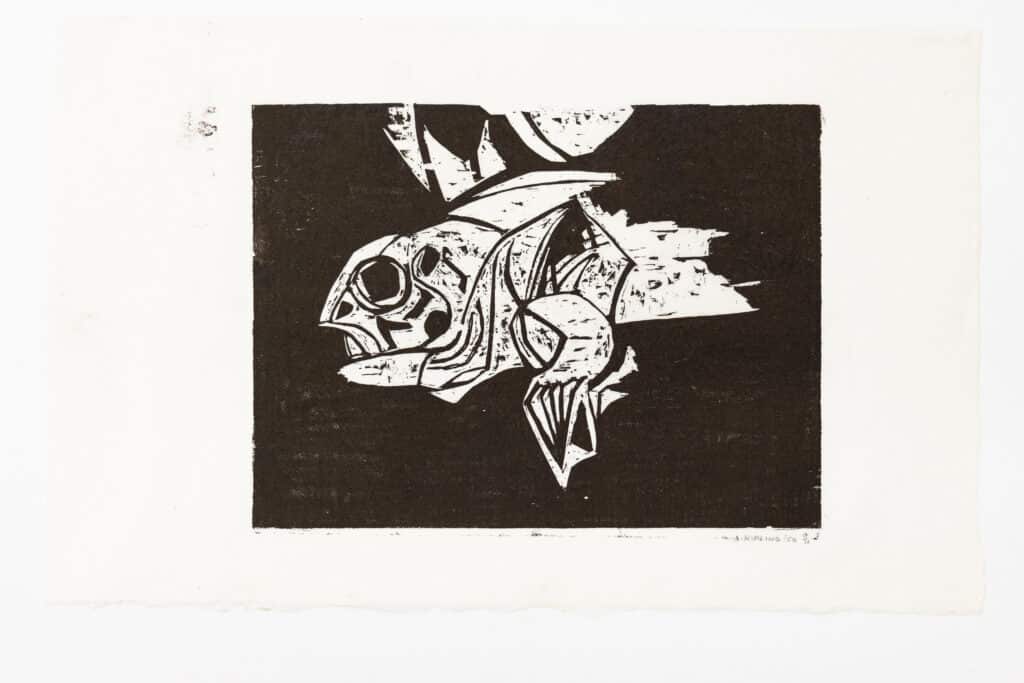

Among the works in the ECU Archives is a 1958 block print created by Ann at what was then known as the Vancouver School of Art (VSA). A print from this edition was purchased early in Ann’s career by the National Gallery of Canada. But Ian notes Ann was withheld from graduating in 1959 on the grounds that her work was too unconventional. Yet when she finally crossed the stage the following year, she did so with honours and as the recipient of numerous awards for artistic merit.

Ian says this somewhat confused response to her work was not uncommon and reflects the degree to which she forged a unique identity among Canadian artists.

“Having made the decision to only work on paper shortly after leaving the Vancouver School of Art, she created a path that was very unusual,” Ian says, noting she was lauded by curators and fellow artists but never found mainstream commercial success.

“Being different and important as an artist and being successful commercially are two different things,” he continues. “And one must be honest — Ann’s work is not easy. You need to devote time to it, and the average amount of time anyone looks at a picture in a gallery is five to seven seconds. But if you’re prepared to spend the time, she makes marks and looks at her subjects in a way no one else does.”

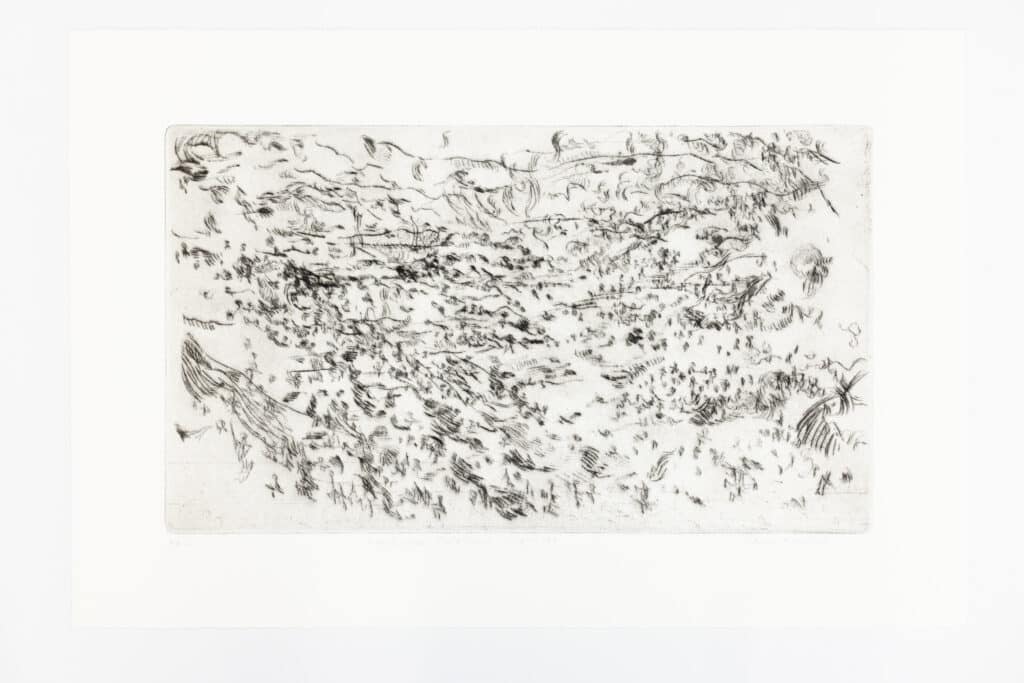

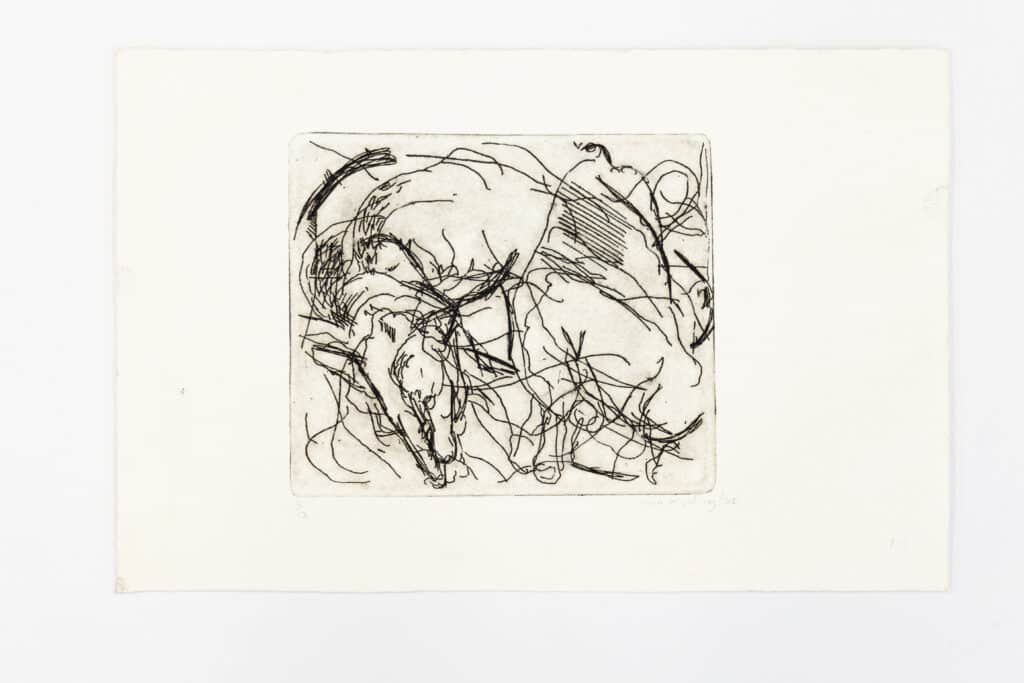

In the 1960s, Ann and her husband, esteemed potter Leonhard Epp (Alum 1960), moved up the Indian Arm. Ann would regularly take her rowboat on the water and, either from aboard the anchored boat or after floating to shore on a raft, etched images into metal plates based on what she observed. After collecting enough of these drypoint plates, she would sneak back into the VSA at night to print them.

“It’s critically important to understand that when she was making these prints out in the landscape, she made them in the landscape,” Ian says. “She never touched them up after leaving the site. The same is true with her drawings.”

A number of these 1960s prints are found in the ECU collection and demonstrate Ann’s custom of returning to a particular subject repeatedly over months or even years.

Artist and ECU faculty member Beth Howe has built entire curricula around taking students to the ECU archives to research the print collection in person. She notes that drypoint etching is one of the first techniques students learn in ECU’s Print Media program. It is both a direct and relatively uncomplicated technique, making it an ideal entry point for Foundation students, she says.

“We are always thinking about how the print collection can be used in the classroom to educate our next generations of artists. Having access to Ann Kipling’s work in person means students can closely examine finished drypoint prints and see how an accomplished artist approached this process and explored it thoroughly,” she says.

“Handling the prints makes that process – and the works – far more alive than a slideshow ever could. It tells a print artist a dozen things immediately that can’t be easily said in words. I am very excited to pull these prints out and discuss them with students and other printmakers at ECU.”

Also included in the ECU collection are a series of prints created in the ‘90s with master printmaker and New Leaf Editions founder Peter Braune, who also studied at ECU.

The ECU collection is among several that Ann’s estate has now placed within a dozen institutions across the country, including the National Gallery of Canada. Ian says he hopes to create greater access to Ann’s one-of-a-kind artistic legacy for future generations, including ECU students.

“Her approach to printmaking is unlike virtually anyone else,” he says. “And the work is demanding because she was demanding of herself. But as Darrin [Martens, curator and alternate executor] has pointed out, if you spend the time, the reward is there.

“I think, particularly in the age of artificial intelligence, the pace of life is so quick. Ann was dedicated to taking things slow, and, over time, the rewards would come. She demands that of the viewer, that same dedication she had from the 1950s through ‘til the end of her life — to make a mark, and each mark is important. In all the prints, in all the drawings, there’s no editing whatsoever. These are her vision from beginning to end.”

More About the ECU Library + Archives

The ECU Library + Archives supports creative exploration, academic work and personal inquiry across the university.

Our library collections focus on contemporary art, media and design, alongside materials that deepen our understanding of art history, cultural theory and critical practice.

The Archives preserves and shares ECU’s rich history, from official records to personal papers.

Our team can guide you in your research, answer questions and connect you with the right tools and resources. We aim to spark curiosity and empower the ECU community to explore, question and create.

More About Print Media at ECU

Engage in immersive studio courses and critical studies that explore print media’s historical and modern facets. Experiment with various printmaking techniques using specialized equipment and facilities, developing a unique artistic practice.

The curriculum emphasizes understanding the global histories of print media and its intersections with fine art, popular culture, mass media, propaganda, marketing and social movements.

Visit our website to learn more.

100 Years of Creativity: The Stories that Shaped Us

As part of Emily Carr University’s centennial celebrations and our ‘100 Years of Creativity’ campaign, we are sharing stories that spotlight the creativity, resilience and impact of our community over the past 100 years. These stories feature the people, projects, places and ideas that have shaped ECU, reminding us of our shared legacy while inspiring the future. By revisiting past milestones and sharing new ones, we honour the many voices that built our institution and continue to guide its path forward.

For more information about ECU 100 centennial celebrations, upcoming events and stories, visit our webpage.