Richard Hambleton | The influential Canadian street artist you've never heard of

Posted on | Updated

Vancouverite and alumnus Richard Hambleton (1975) passed away in 2017, leaving behind a legacy of subversive art that helped shape the face of street art as we know it today.

Steven D'Souza, CBC News

Published January 1, 2018

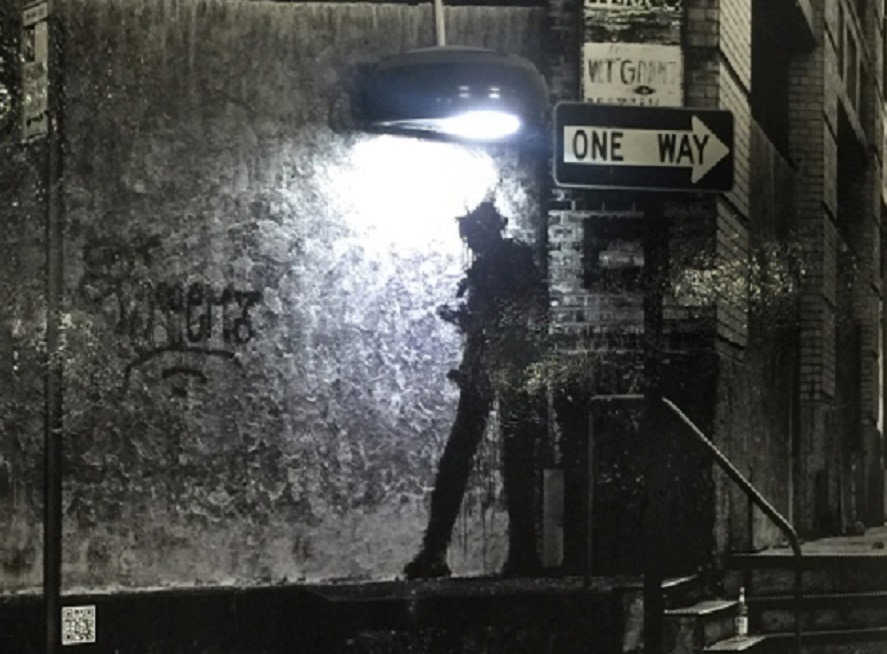

Oren Jacoby will never forget the feeling when he first encountered the shadowy figure staring back at him menacingly in a dark, graffiti-filled alleyway in New York's Lower East Side in the early 1980s.

"The first time you saw one you'd practically jumped out of your skin because you thought somebody was lurking in the alleyway and was about to grab you and take your money," the filmmaker recalled.

The lifelike painted black figures were popping up all over the neighbourhood, and in other parts of the city, and Jacoby's reaction was exactly what Canadian-born artist Richard Hambleton — who would come to be known as the Shadowman — was looking to evoke.

"Richard had this notion of art as a provocation, as something that would grab a hold of your psyche," said Jacoby, director of the 2017 documentary Shadowman, which chronicles Hambleton's life.

Hambleton, 65, passed away on Oct. 29, 2017, at an apartment in New York City, after a career remarkable for its bold creativity, longevity and constant conflict with the fame his work attracted.

He's been called the Godfather of Street Art. His work laid the foundation for French artist Blek Le Rat and current practitioners like Banksy, who — as Hambleton's followers will tell you — considers the Canadian an important influence.

Hambleton was born in Tofino, BC, studied painting and art at Vancouver's Emily Carr Institute of Art (now the Emily Carr University of Art and Design) and helped found the former PUMPS Centre for Alternative Art.

His work first gained notoriety in 1976, when white-painted outlines of human figures began appearing on the streets. With the public, police and media scratching their heads over the crime-scene-like depictions, Hambleton then created the pseudonym R. Dick Trace-It to solve the non-existent crimes, complete with "Wanted" posters for fictional felons. At the time, no one knew they were participating in an art project he'd call Image Mass Murder.

By 1979, Hambleton — handsome, blue-eyed, with an enigmatic charisma — had travelled across North America and painted more than 620 outlines. The San Francisco Chronicle called it the work of a "sick jokester."

Hambleton ended up in New York, where, he told friends, he was going to jump from the Empire State Building onto a large white canvas. Luckily, that never happened. Instead, he started painting the shadowy figures for which he would become best known.

"I'm not trying to make a specific statement with them," Hambleton told Time magazine in 1984. "They could represent watchmen or danger or the shadows of a human body after a nuclear holocaust or even my own shadow.

"But what makes them exciting is the power of the viewer's imagination. It's that split-second experience when you see the figure that matters."

He painted 450 of them across New York and embedded himself in the Lower East Side's art scene alongside contemporaries like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

'Lived outside of the box'

At his peak in the mid 1980s, Hambleton's work was better known and selling for more than that of Haring or Basquiat. He held exhibitions in New York and across Europe, even adding his figures to both sides of the Berlin Wall. Andy Warhol repeatedly asked Hambleton to paint his portrait, but the mercurial Canadian never obliged.

Despite that fame, however, by the early 1990s Hambleton began to retreat from the spotlight. He battled drug addictions — particularly heroin — and a fear of the art industry and galleries. His paranoia, in part, was fuelled by the deaths of Haring and Basquiat but also by his aversion to the spotlight.

"All he wanted was to do his art with no constrictions. He lived outside of the box, kind of like a nomad," said Kristine Woodward, co-owner of the Woodward Gallery in New York.

"He always wanted his art to be more important than himself. It was always that way. It was never about him; it was always about his art," added John Woodward, Kristine's husband and gallery co-owner.

Hambleton would move from apartment to apartment, often trading artwork for rent and food, at times homeless. He once was given a chance to live in the Trump Soho Hotel in exchange for some paintings. Six months later, he was out, trashing the apartment before he left.

"Richard was not a conformist, and so if there was a rule and regulation [where] he was living, he would trash the space," said Kristine Woodward, a former critical care registered nurse who also helped care for Hambleton beginning in the late 1990s.

For years, the couple put Hambleton up in hotels and studios, often covering his legal fees when he was evicted.

Later success, and demons

In 2007, the duo staged Hambleton's first solo exhibition in 22 years. Then in 2009, a pair of young art entrepreneurs further coaxed Hambleton out of the shadows with a gallery show sponsored by Giorgio Armani.

But the comeback was short-lived, as the artist once again retreated to the shadows. He was now suffering from scoliosis and cancer that was eating away at his face.

This is when documentary filmmaker Jacoby encountered Hambleton. "Quirky doesn't do it justice," he recalled.

"Richard was an incredibly complex personality. He could be charming, he could be charismatic. He could also be unbelievably manipulative."

Jacoby notes the bittersweet timing of Hambleton's death: days before one of his paintings was put on display at New York's Museum of Modern Art and just a few weeks before Jacoby's Shadowman debuted in New York cinemas.

Hambleton, who had seen the doc earlier in the year when it screened at the 2017 Tribeca Film Fest, kept working and painting until the very end, the filmmaker said.

"There were demons or ideas or things that was being expressed through the work he was doing, right up to the day he died."

John Woodward, who has spent decades attempting to catalogue Hambleton's oeuvre, says while some works were lost due to the artist's nomadic existence — pieces often destroyed by angry landlords — there is still a wealth of material out there.

He said he discovers new pieces every week thanks to the way social media has allowed lovers of Hambleton's work to come together. He's also had an increase in calls and emails from gallery owners worldwide.

One piece he recently rediscovered was something from his own collection: an image from a magazine that Hambleton had told Woodward not to reveal until after his death. It shows a young Hambleton posing in the arms of the Angel of Victory statue in Vancouver, his lifeless body pierced by paintbrushes.

"This is how Richard wanted to perceive himself at the time of his death," Woodward said of the artwork, which Hambleton created in 1974.

"Richard always thought ahead. He was one step ahead of everybody, including how and what he created," Woodward said. "That's the genius behind his work."