The Creative Potential of Public Space

Posted on | Updated

An ECU research team seeks out innovative solutions to real-world matters situated in shared spaces

Public spaces most often change slowly and incrementally, say Laura Kozak and Charlotte Falk, Research Associates at Emily Carr University of Art + Design’s Living Labs.

So what happens when an entire area — such as the Great Northern Way District where Emily Carr is now located — undergoes a sudden, rapid transformation?

“In the case of Great Northern Way, a really intense period of redevelopment has brought a lot of changes all at once,” Laura recently told ECU.

“This has meant that the ecological, Indigenous and industrial histories of the site have been overwritten in a way that makes the public realm feel a bit immature: lots of new, pristine surfaces; lots of new people who don’t know each other very well yet; some missing amenities; and a little bit of an absent sense of personality.”

With that in mind, Laura and Charlotte (alongside Research Assistants Jean Chisholm, Marcus Dénommé, Celine Hong, and Augusta Lutynski), recently developed a series of human-scale interventions for spaces around Emily Carr’s new campus. Their project — which also involves a related initiative in Prince George, BC — is called Designing for Public Space.

The interventions the researchers developed and installed were designed to encourage passers-by to engage with the public spaces through which they traveled, and to provide opportunities for creative reflection and interaction with facets of the landscape which might otherwise go unnoticed.

Great Northern Way Trust — the foundation established by the University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University, Emily Carr and the British Columbia Institute of Technology to manage the Great Northern Way lands, assets and income on behalf of the four institutions — has been “working hard to enrich the public sphere, and has been a very supportive partner in this project,” Laura noted.

After conducting research which included extensive mapping of the Great Northern Way (GNW) District, and a survey of individuals who use the area, Laura, Charlotte and their team developed five initial concepts for addressing the site’s conditions and opportunities.

The intent of each concept was to “bring identity and activation to the site; through each we asked who gets to have a say in the shaping of the public realm. How might we give some voice to those who are marginalized in these processes of redevelopment?”

A pair of concepts were selected from an original slate of five. From there, the team generated a series of rapid prototypes, gradually refining design details including material palette, assembly and placement.

For the intervention entitled Optical Tactile Acoustic, they built and installed a series of interactive and kinetic objects mounted on wooden stakes in the areas around GNW identified as key thoroughfares and meeting points. Some were intended for tactile interaction, some for visual delight, while others formed a “corridor of sounds” along the busy bike path, enriching and activating the commuter route to the southwest of Emily Carr.

“It was great to watch friends and strangers interact with OTA: lots of pausing to look at the stakes, and hopefully the slowing down also caused different consideration of the site as a whole,” she said.

“In another part of town, I overheard a dad telling his son about the corridor of sounds along the bike trail. This was one of our ambitions: to give the site a bit of a special identity for those here but also for those passing through.”

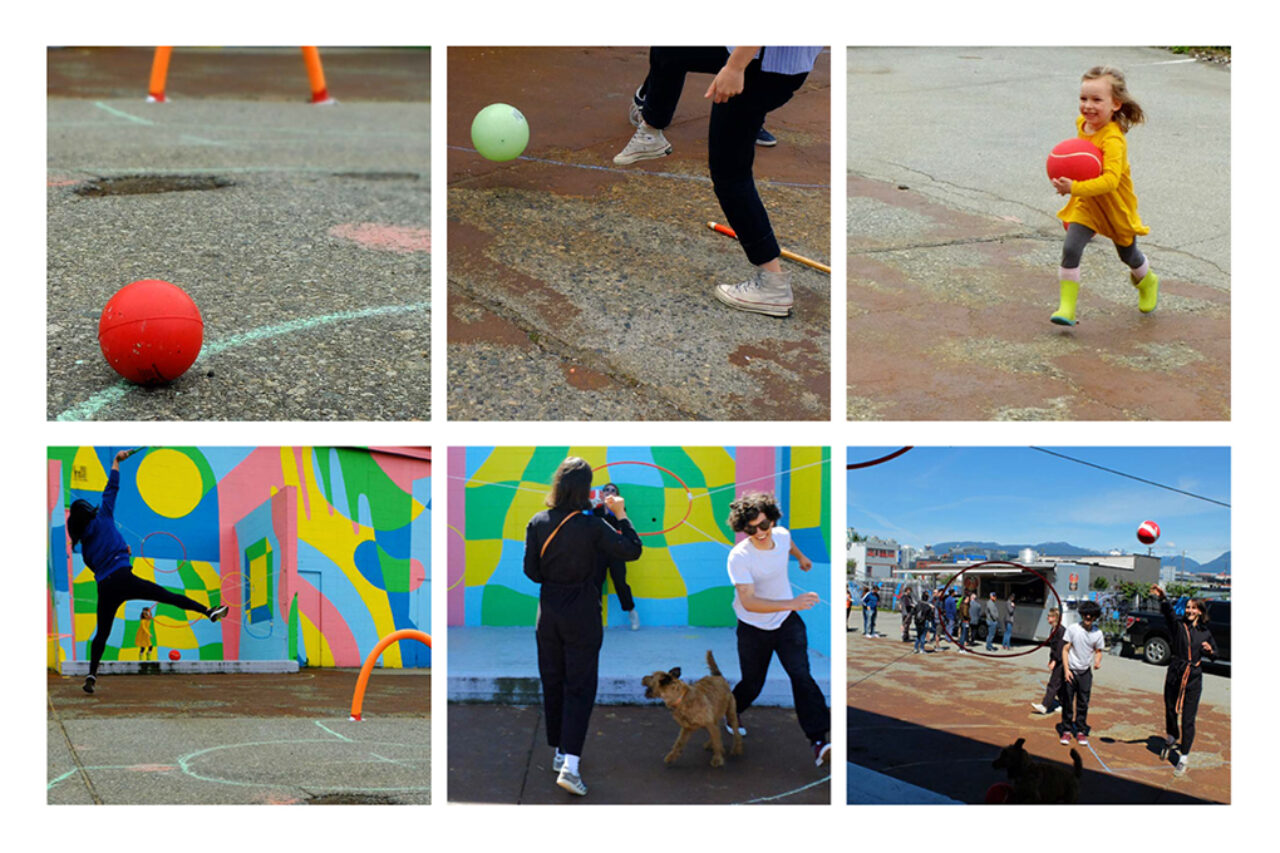

The second intervention, entitled Shape Loop, included hoops, balls, chalk lines and ropes arranged on the north side of the GNW campus area. The installation was designed to prompt spontaneous play, exercise and creative interaction, while maintaining a minimal impact on the buildings and existing landscape.

It was “exciting to witness unexpected combinations of people interact” with Shape Loop, Charlotte said. At one point, she noted, a four-year old child, UBC students and tech workers all played line tag, wall ball and other invented games together.

“This is a kind of site activation and social mixing that we think could happen much more as this concept develops,” she said. “It also brings forward opportunities for play and exercise, which our site survey revealed to be desired for this area.”

A more permanent version of Shape Loop would contribute “to a sense of placemaking,” and heighten “social mixing amongst different kinds of site users through active play and exercise,” suggests the team’s final report.

In Prince George, in February, the team also programmed two workshops called Story Sticks with students in grades four through six, from Nusdeh Yoh School and Harwin Elementary, held at Two Rivers Gallery.

Using a range of simple, colourful materials, students were encouraged to use both their imagination and personal experiences to think about their own roles in the activation of public space.

Working from the definition that public spaces are “spaces you don’t need to pay money to access, and spaces you don’t need to be invited into,” the workshops “prompted young people to consider matters of public space through the lens of their own stories,” Laura said.

This research project has also led the team to "questions about public space in relation to Indigenous rights: if we understand public space as ‘not private space’ then we might understand both as construct of colonialism.”

The next phase of the project will be in Prince George, and includes working with the Aboriginal Housing Society, which is currently undertaking the development of a major public housing complex in the city. The hope is to work with government, tenants and the architectural team to look at how public spaces within that shared community might be actively considered as important signifiers of identity and community agency.

Meanwhile, the Designing for Public Space final report was submitted just a few weeks ago to the Great Northern Way Trust. Laura and Charlotte are keen to continue working with GNWT, and that the research to-date might have an influence on the GNW area as the new Broadway SkyTrain line — and other projects — continue to transform the public spaces around Emily Carr.

According to Graham Winterbottom, Director of Real Estate and Community Development for the Great Northern Way Trust, this goal aligns squarely with the aims of his organization.

"As we transition to a new phase of development, the Trust is looking to establish new ways to activate and enliven the public realm to create opportunities for students and employees to informally connect and enjoy themselves on the site," he told ECU.

"We were excited to work with Kate, Laura, Charlotte and the rest of the Living Labs team to generate some new and innovative ideas to activate our public spaces. Moving forward we hope to implement some of these ideas both as temporary installations and permanent works upon the completion of the Broadway Subway Project."