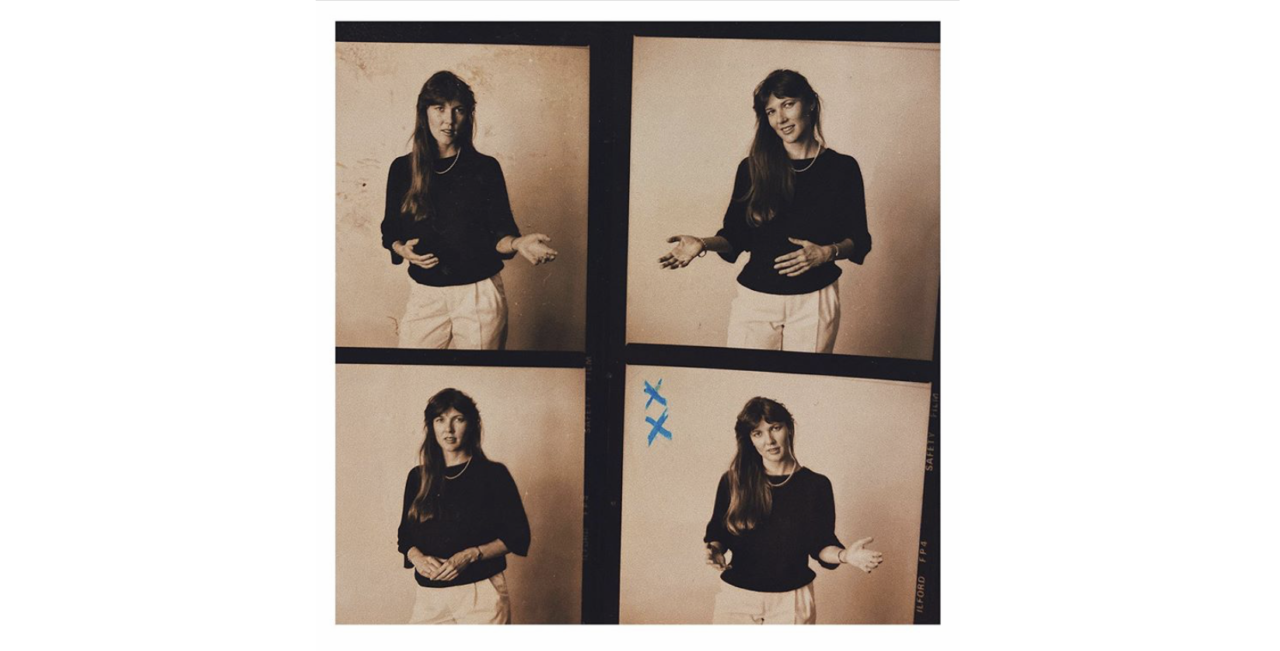

Designer Karin Jager on Community, Self-Discovery and Her Nobel Peace Prize Connection

Posted on | Updated

The accomplished creative professional and educator credits her success to a lifelong emphasis on authentic human relationships.

In October, when the United Nations’ World Food Programme (WFP) was announced as the recipient of the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize, the multinational nonprofit bore the same logo it had been using for decades — a stylized hand clutching wheat, rice and corn, encircled by a laurel wreath.

The iconic image has lasted for so many years largely due to its incisive summation of the WFP’s mission: “saving lives and changing lives, delivering food assistance in emergencies and working with communities to improve nutrition and build resilience.”

But behind the emblem for the organization lauded by the Norwegian Nobel Committee for its “efforts to combat hunger, for its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict” is the story of a young designer.

In 1986, Karin Jager (1985), now head of the Graphic + Digital Design department at the University of the Fraser Valley, was freelancing for Environment Canada (among other clients), having just begun a burgeoning career as a design professional.

She’d interned as a graphic designer for the federal agency while between her third and fourth years at Emily Carr, then known as the Emily Carr College of Art and Design.

“A couple of years later, Environment Canada’s director of communications, Paul Mitchell, ended up moving over to the World Food Programme as the executive director of communications,” Karin recalls. “Paul invited me to come to Rome and design that logo.”

In those days, the fax machine was bleeding-edge technology, Karin says, and design work was conducted almost entirely by hand. Photomechanical transfer cameras and sheets of paper pasted on boards were a daily part of the practice. So, materials in hand, Karin hopped on a plane to put pen to paper on a brand that would endure well into the new century.

“The World Food Programme was really an exciting project for me because they were doing so much good for the world: helping vulnerable people, and helping mitigate really extreme political situations and environments, and climate issues; at that time, severe drought and conflict caused extreme famine in some countries,” Karin says.

“Every so often, my students will discover the logo, and they’ll know it’s my piece. And they’re pretty surprised by it.”

But more than just a story of an exceptionally keen eye, Karin’s is a story that is emblematic of the key role relationships play in the success of a career in the creative world. The fact that a former colleague was the one to invite Karin to take on the WFP design job is a dynamic that has played itself out repeatedly in the 30-plus years since she boarded that flight to Rome.

When Karin first graduated, she moved directly into freelancing, which provided an early lesson in the importance of building contacts.

“It was really hard to get a job at that time,” she says. “There was a huge recession taking place in the early ’80s in Vancouver, so most of us were struggling. I was lucky because I had that internship between years three and four, and from it, I made tons of connections and started working a lot in the nonprofit design industry.”

“When you’re in a creative career, there’s no prescriptive path ... That’s what makes it so exciting: you just never know what you're going to be doing.”

Clients included the Canadian Cancer Society, the Red Cross Society, the Arthritis Society, CBC, and the National Film Board. Karin quickly developed a reputation for treating difficult subjects with sensitivity and dignity.

“I worked on quite a few extreme issues,” she recalls. “Homophobia was a really, really big issue at that time. The AIDS crisis was huge. So many of my classmates passed away because of the AIDS epidemic. It was a very, very difficult time … I worked on sex education, child abuse, PMS, teenage pregnancy. A lot of issues that people never really talked about.”

Quite simply, Karin says, one client led to another. And while many of the technical skills Karin now possesses were learned post-graduation, as a working professional, she notes that she has always relied on some of the key lessons she learned at Emily Carr — specifically, an emphasis on conceptual development, thinking deeply about every choice she makes on each project, and understanding the target audience.

Meanwhile, against a pre-Internet social and cultural backdrop marked by soaring interest rates, crushing unemployment, and future-looking optimism for the redemptive power of technology and free enterprise — embodied by the hodgepodge techno-utopian visions of Expo ’86, widely viewed as the moment Vancouver began its transformation from sleepy coastal port to gridlocked international hub — Karin continued to forge her path.

The ’90s saw Karin shift to corporate communications. Halfway through the decade, she received a call from Capilano College for what turned out to be a job interview. While Karin would go on to teach at Capilano for several years, the design program was eventually cut “because we weren’t keeping up with technology,” says Karin.

But following the program’s scuttling, the college recruited Karin to lead a task force to create a brand-new program, primarily because she was one of the few faculty members running an actual design business. The IDEA program — now the award-winning IDEA School of Design — was the result. And for Karin, this achievement further underlines the value of community relations.

“Everything I did at Capilano was just one connection after another,” she says. “Just networking and working with other people and valuing relationships, and also being very entrenched in industry practice through professional associations like the GDC, and also with my community. That was really, really important. I found that things would just happen.”

With the 2008 government decree that granted university status to six post-secondary institutions — including Emily Carr — Karin decided to pursue a graduate degree. During enrollment in the Master of Education program at Simon Fraser University, Karin conducted a massive research study on Canadian design programs. Of the roughly 80 programs in Canada, 50 responded, Karin notes, offering her a robust data set for her research project.

”There’s no playbook really, other than being true to yourself and, and being authentic and building those relationships.”

The study also prompted the University of the Fraser Valley (UFV) to ask Karin for help developing its own new design program. Through her work as a consultant with UFV, Karin pursued a full-time position to launch the program, and continues to move design education forward to this day. Karin points to this more recent move as another example of the kinds of “serendipitous moments” that have defined her “wonderful” career.

“I’ve had a lot of great things happen, and I believe that’s about relationships and building reputation,” she says. “One thing just leads to another, and I think what’s most important is that, when you’re in a creative career, there’s no prescriptive path. It’s such an expansive field, and it’s always changing. That’s what makes it so exciting: you just never know what you're going to be doing.”

A sabbatical in 2019/20 saw Karin studying “future-focused design education,” she says, but also drove home how a creative career continues to offer opportunities for self-discovery, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and constant learning.

“There’s no playbook really, other than being true to yourself and, and being authentic and building those relationships,” she says.

“When you’re out in the industry, or when you’re out in the world, you’re never, ever working alone … You’re always learning, and you’re always complementing other areas and sharing knowledge in ways that you never expect. I think that’s what makes us grow so much.”