Avi Farber Forges Connection with Wildfire and Clay

Posted on

The artist and ECU MDes student maintains an ecology of practices in service of a deeper engagement with design and with the world at large.

“I want to tell you the story about this object and how I know the land through it,” Avi Farber tells an online audience during the 2021 Canadian Association for Graduate Studies (CAGS) Virtual Symposium.

Onscreen is a rough vessel — a flask, the artist and Emily Carr University Master of Design student tells us. The object is 3D-printed from clay, which has been harvested by hand from the earth. Its pale form is streaked with black — traces of the wildfire that hardened it.

“It’s a metaphorical object that I use to think about how we relate to wildfire, [and] to emerging technologies,” Avi says. The flask is also emblematic of Avi’s thesis work, Making Kin with Wildfire. The thesis details the current preoccupations of his “relational design practice,” including the relationships people have with fire, with stories, with land, and with “emerging” technologies such as 3D printing.

Avi Farber's 3D-printed, wildfire-fired clay flask.

As Avi speaks, it quickly becomes clear that his diverse body of work forms something like an ecology of practices. In each of his roles as a production potter, designer, ceramicist, photographer and firefighter, Avi works in unique but complementary ways with the same materials.

“At the same time I was working with fire in the kiln, I was also working with fire in the landscape as a wildland firefighter, and I was building a relationship with fire in the landscape,” he tells us.

His work as a potter, for instance, is about creating objects by harnessing fire and earth. His work as a firefighter, meanwhile, often brings him into contact with the destruction of objects and earth by fire. In this way, Avi’s manifold perspectives point very naturally to the existential nature of human relationships to fire, to land, and to things. (To bring attention to both the ways that fire may bring loss as well as regeneration and beauty.)

“My project hinges on ideas of thinking about how the objects we make affect the world that we live in,” he tells us. This notion inverts the aims of traditional design practice, which historically sought to create solutions for easing and enabling the human experience in and of the world, rather than necessarily considering the world itself. This approach is very much informed by Avi’s firsthand experience of fire-ravaged human habitations.

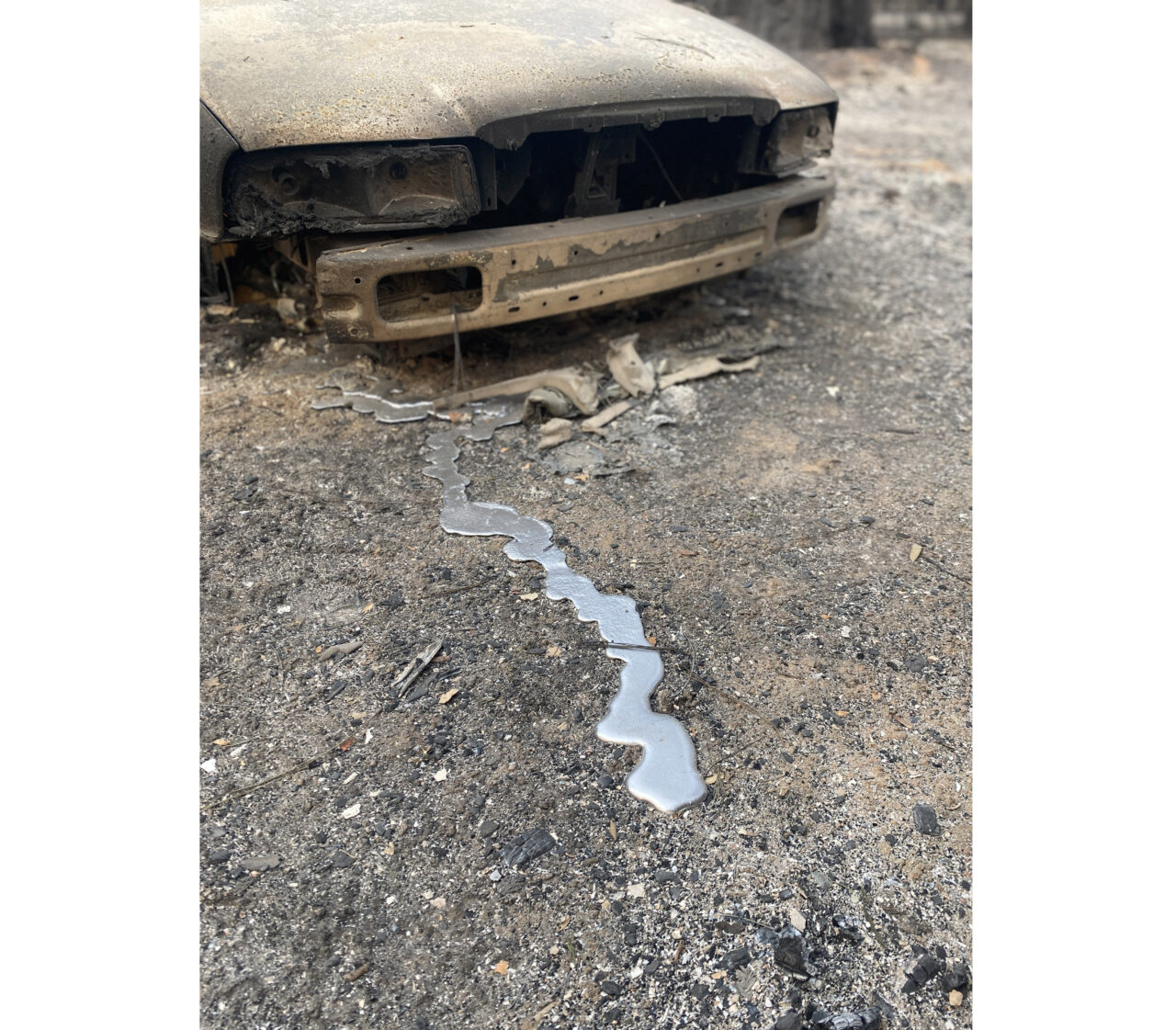

“Part of my research was going into areas that had been impacted by wildfires [and] thinking about how our designed places are affected by wildfires and how our objects might mediate that relationship,” he says, pointing to an image of a husk of an automobile leaking silvery fluid into the dirt — a river of aluminum, he tells us, liquified by the extreme heat.

“By placing the flasks into these burned areas (or areas that were going to be burned), I’m trying to create connections between those worlds.”

The husk of an automobile leaks silvery fluid into the dirt — a river of aluminum, Avi tells us.

Fire is both regenerative and destructive, Avi says. It has been used for centuries by farmers to remediate exhausted fields. It has also razed entire communities. Fire’s relationship to human-designed objects, then, reveals a history of people’s relationship to the land.

Linking this perspective to the work of one of his fellow students, Avi notes artist and ECU MDes candidate Julie van Oyen had only a short while earlier suggested the “flesh of the earth is us,” while presenting her own work.

“I like thinking about [that],” Avi says, “How fire is part of the land and how we’re all connected, how we can build a relationship with fire, a deeper relationship with fire that might connect us to the places around us and how we might know them.”

Harvesting clay with bare hands is another way to gain closer connection to the land, Avi says. Putting that clay through a 3D printer then implicates technology in this process of knowing. Coming full circle, an object such as Avi’s 3D-printed wildfire-fired clay flask represents a convergence of all of these ideas.

Two more examples of 3D-printed clay flasks by Avi Farber.

It feels fitting that Avi’s work suggests a blurring of the lines between the professional and the personal; between the practice of design and acts of pure knowing or being. Speaking later via email, Avi tells me his research rarely feels like “work.” Rather, it’s a record of a pursuit of subjects that bring him joy. This is a function, he adds, of an emphasis on “relationality” — a focus on relationships between people, places, context, cultures, movements, objects and environments.

“When we embrace these interconnections it can be very rewarding, and hopefully benefits those whom our work engages as well” he says. Art and design, in particular, are activities that naturally incline practitioners to be of service to the world around them.

“One thing that’s important about design is that it really

pushes us to focus on what we believe in. And I think that will

naturally help you be in what you’re doing,” he says. “We dig

into the problems in the world, and once you have seen everything that

you are connected to that needs your help, the decision to be engaged is

easy.”

Photo documenting Avi Farber's work as a wildland firefighter.

Avi’s thesis will be available via the Emily Carr University Library. Find out more about Avi’s art and design work at avifarber.com.