Diyan Achjadi Slows Down the Act of Looking to Uncover the Movement of Knowledge

Posted on | Updated

The multidisciplinary artist and ECU faculty member reflects on the ‘decorative unconscious,’ limitations as provocations, and materiality as an antidote to screen time.

Rain turns to sun, and then water rises. Geometric forms appear, rendered in wet paint that dries in moments. A figure emerges, its head encircled by moths. Colour and shape, movement and sound; a laconic flow of images that merge into and out of one another in a muted cycle that is both beguiling and gently melancholy.

I’m watching Diyan Achjadi’s recent animation, Hush, which has been showing on the Urban Screen at Emily Carr University through spring and summer, 2021.

According to the award-winning, multidisciplinary artist and ECU faculty member, the work provided something like a necessary counterbalance to the endless amounts of time everyone began to spend interacting through screens over the past year and more. Each frame of Hush was painstakingly rendered by hand in watercolour and ink, between August, 2020, and January, 2021.

“I wanted to see if I could make something that felt intimate, slow and tactile for such a large-scale and public screen,” Diyan says of the work.

“As time seems to move in a strange pace — painfully long in its duration while also feeling so fleeting — so do these animated drawings, compressing hours of the slow labour of placing water and pigment on paper, to mere flickers and seconds of viewing,” she wrote of Hush in an earlier text.

Animation still from Diyan Achjadi's 2021 short film, Hush.

The compression of time and labour is a theme that likewise animates another ongoing project, MIDDplace, which draws in three artists Diyan met in graduate school 20 years ago. The quartet, who live “scattered between three nations and two continents,” have been exchanging large-scale drawings by mail, each taking a turn with the other’s drawing until all four artists have worked on all four drawings.

Originally intended as a fairly brief exchange followed by an exhibition in 2020, the true impact of the pandemic overturned any expectations with which the project may have started. Working with a brush and paint and ink also drove home the importance of physical materials and processes to Diyan’s practice.

“What we did not anticipate was how much this project became a gift to us during this strange, distressing, and isolating time,” Diyan tells me. “There was the joy in receiving a package, and opening it to unroll a beautifully considered drawing that carried the traces of the gestures of friends far away. It became a way to have a conversation with each other as we responded to what we saw in front of us, and built upon each other’s marks.”

While these two projects only scratch the surface of Diyan’s decades-long practice, they point to a thread that can at least tenuously be drawn through much of her work: the power of overlooked images to reveal the circulation of ideas at the level of culture.

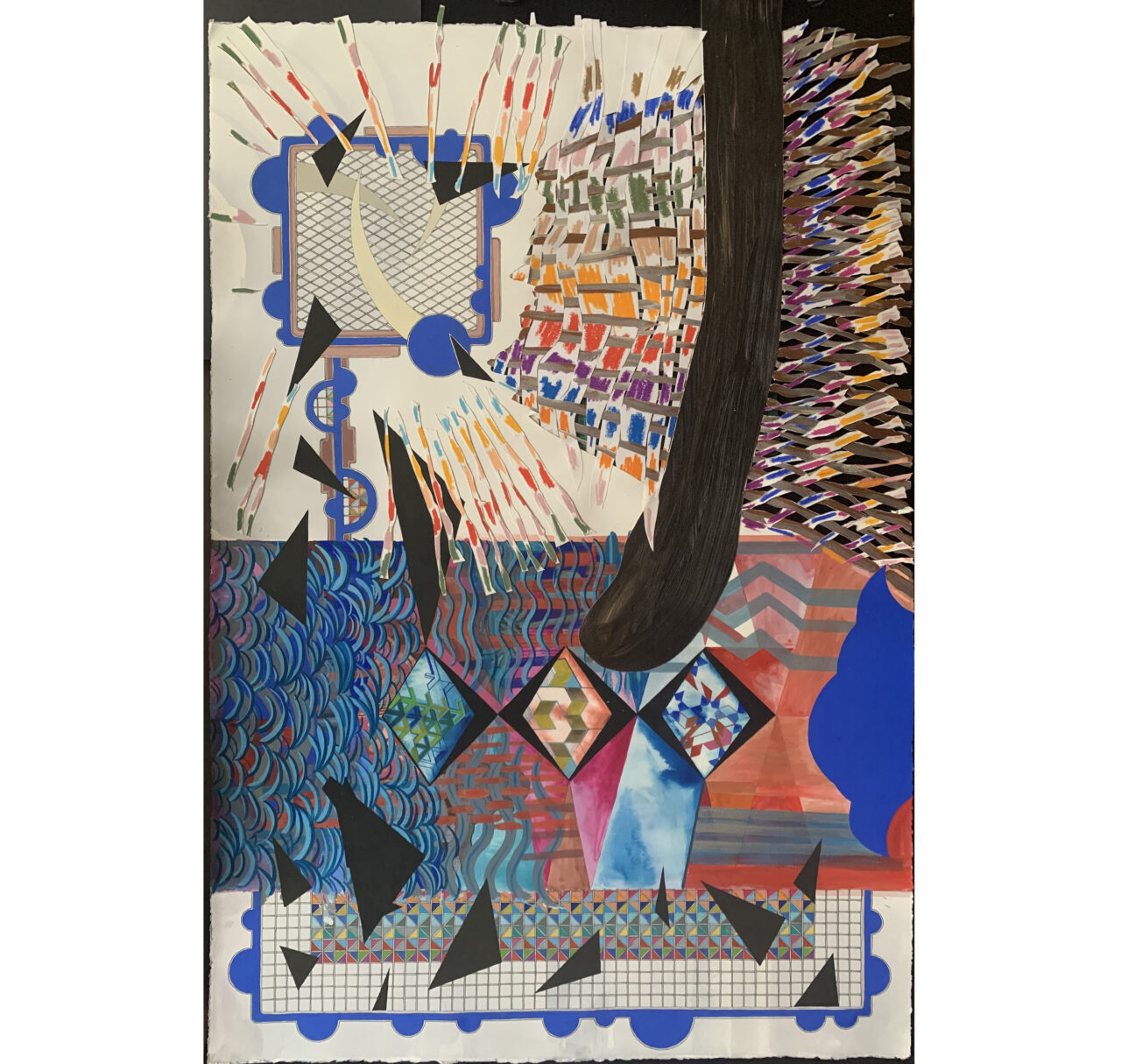

MIDDPlace (Melissa Manfull, Ilga Leimanis, Doreen Wittenbols, Diyan Achjadi), Untitled Drawing 1 (Diyan – Doreen – Melissa – Ilga), 2021. Mixed media collage on paper.

Frenetically but Also Closely

“I look at a lot of things … frenetically but also closely,” Diyan says into a microphone aboard a moving bus rattling through downtown Vancouver on a grey winter day.

It’s 2019, and Diyan is one of five artists selected to participate in the year-long How far do you travel? initiative which wrapped their artworks around 30 Translink buses in the City of Vancouver.

She is in conversation with Kimberly Phillips, then curator at Vancouver’s Contemporary Art Gallery (CAG), a partner in the arts initiative. (Since July 2020, Kimberly has been the Director of SFU Galleries at Simon Fraser University). As part of Diyan’s contribution to How far do you travel? — titled NonSerie (In Commute) — she is delivering a standing artist’s talk aboard a double-length bus covered entirely in her artwork. In this way, she and several dozen audience members explore Diyan’s practice while travelling within the artwork itself.

But for Diyan, this link between the movement of bodies and the movement of ideas goes beyond the local transit route, or the sharing of knowledge with audience members at an arts event. Diyan is “fundamentally concerned with print media’s profound role in the transit of knowledge throughout the world,” according to the CAG’s project text.

Partly, this reflects Diyan’s cosmopolitan upbringing. In her bio, the Jakarta, Indonesia-born artist notes she spent her “formative years … moving between multiple educational, political, and cultural systems.”

This expansive sociocultural perspective as well as Diyan’s fevered-yet-focused looking are evident in NonSerie’s “swirling, riotous reconfiguration of historical illustrations that depict an imagined Indonesia — its landscapes, architecture and fauna — from the perspective of the 17th- and 18th-century Dutch settler.”

Diyan Achjadi, NonSerie (In Commute), 2019. Vinyl bus wrap. Commissioned for the How far do you travel? public art initiative.

The Decorative Unconscious

All of these influences and concerns are perhaps inextricable from Diyan’s decades-long engagement with printmaking as a powerful — and sometimes underestimated — medium for culture-making. (Her Instagram handle, @printnerd, is a low-key hilarious nod both to her hard-earned fluency as a printmaker and to her fascination with overlooked historical image traditions such as Chinoiserie wallpaper and textiles and other “background imagery” that often falls under the term “decorative arts.”)

For Diyan, it isn’t just the monolithic, unforgettable images that influence people and cultures. Background images — ephemera pulled from the “decorative unconscious” — exert an equally powerful influence. Such images “start to inform our consciousness about what is normalized,” and reveal the “underbelly of the colonial imaginary,” as she noted to the audience on the bus.

“I am interested in how we are formed / informed / misinformed by the visual matter around us, and often unconsciously so,” she told me recently in an email correspondence. But the goal isn’t to prescribe some new kind of relationship to visual culture, she cautions. Instead, Diyan aims to uncover how that unconscious — or uncritical — consumption of imagery can be interrupted.

“What might be a way to draw attention to something,” she asks, “to invite questions (rather than pose a statement or foregone conclusion)?”

Diyan Achjadi, What is Unseen, 2021. Ink, gouache, graphite, and gudy-o on paper.

Slowing Down the Act of Looking

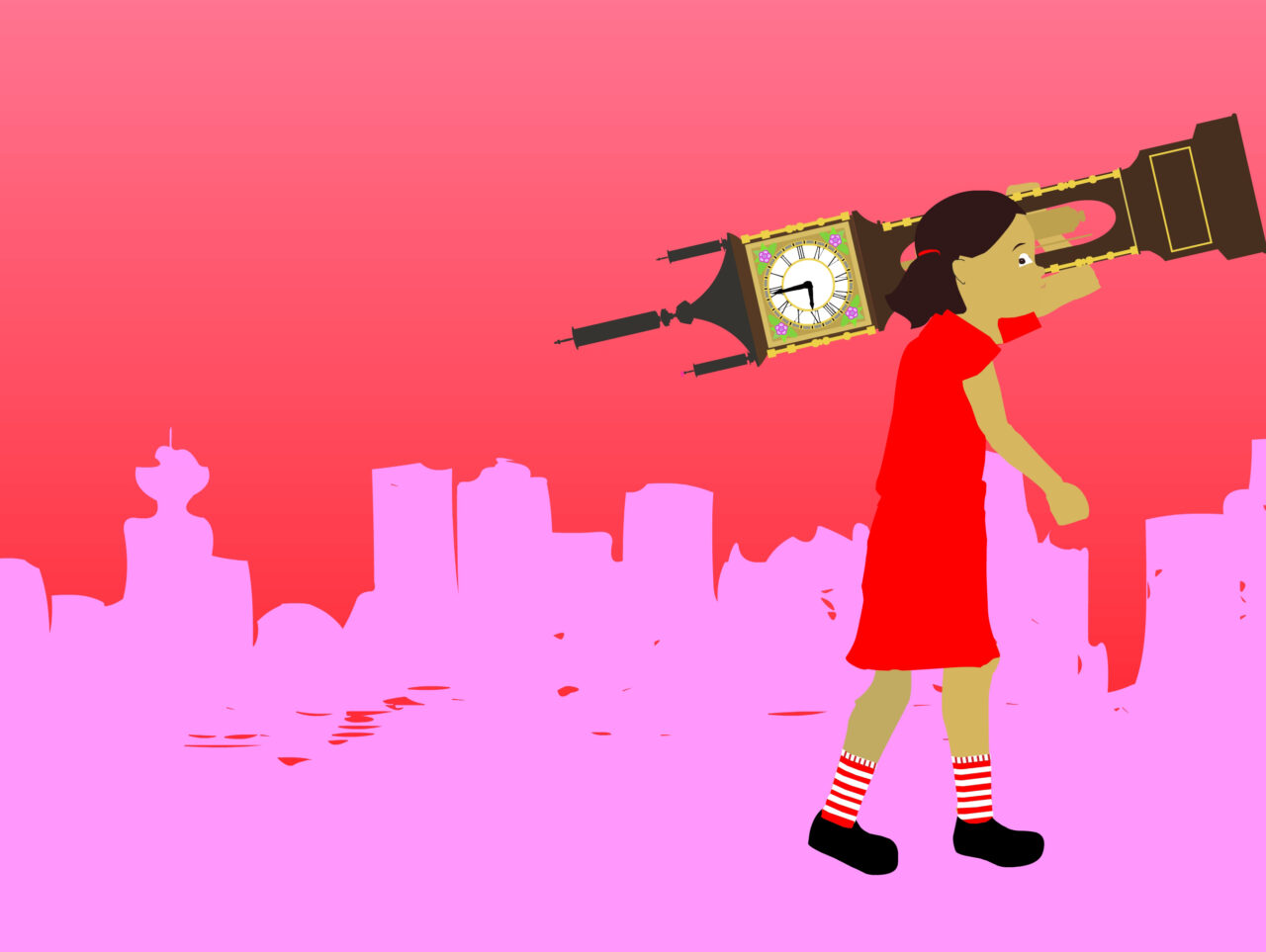

This inquiry infuses works such as the 2011 series of animated shorts Girl in the City, as well as the more recent series of public works, Coming Soon! (Both works, incidentally, were commissioned by the City of Vancouver Public Art Program.)

Girl In The City follows the eponymous Girl as she encounters and collects familiar Vancouver sites and structures. The series of 30-second vignettes (which, Diyan notes, is roughly the length of an average television ad) first showed on the public screen high above the intersection of Robson Street and Granville, in Vancouver’s downtown core, shortly after the Winter Olympics had come and gone. The work was influenced by the dramatic changes those Olympics wrought on the cityscape — both during the Games, and forever after. It also plays with the language and cadence of advertising, dovetailing with the work’s display on a public screen that “one might encounter … whether or not one wanted to.”

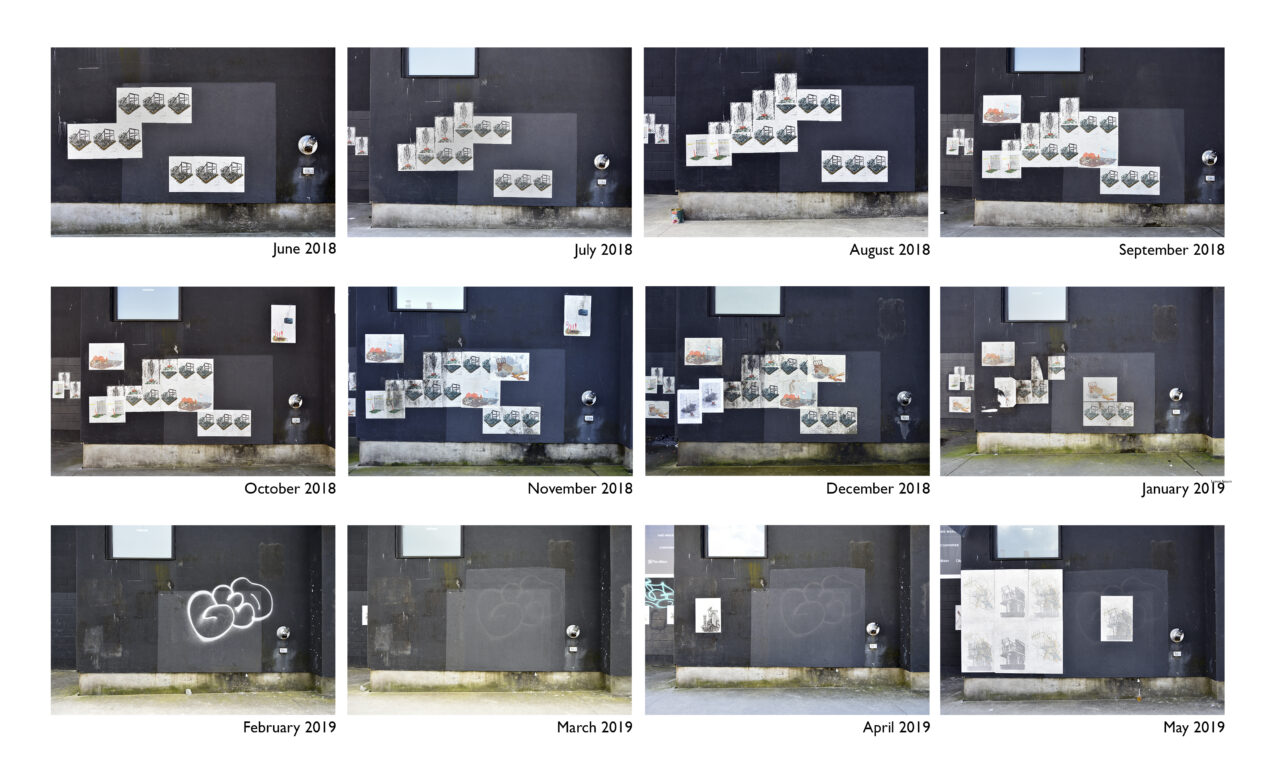

Coming Soon!, meanwhile, takes some of the dynamics of Girl in the City even further, albeit with a very distinct formal approach. The year-long project saw Diyan install a series of laboriously printed posters on construction sites around the Railtown, Mount Pleasant and Riley Park neighbourhoods. Coming Soon! is uncompromising in its exploration of themes including labour, site, local context, value and the violence of erasure and gentrification. It is also “anti-monolithic,” “anti-monumental,” and “subtle, easy to miss,” according to the CAG’s Kimberly Phillips.

Animation still from Diyan Achjadi's Girl in the City, 2011.

Both Girl in the City and Coming Soon! provide examples of how Diyan seeks to lay bare the unconscious influence of imagery. As with Non Serie, the works exist in spaces Diyan identifies as potential “points of interruption, as they often contain mostly advertising or announcements (the video screen, the bus wrap, the construction fence),” she tells me.

“The duration of these projects also allowed for repeat encounters, potentially slowing down the act of looking, and in the process becoming something that one is more conscious about seeking out.”

This process of encouraging slower and repeated looking runs entirely counter to the disposable glance-then-swipe consumption behaviour with which so much of modern image culture is treated. Slower looking also forges a link between the digital screen and the physical print, which, Diyan notes, are grounded in a shared history — the history of communication technologies. The availability of these tools throughout history has directly impacted the ways culture — and therefore society — has taken shape. As artistic mediums, they also share a common antecedent in drawing, making them ideal for Diyan’s investigations of their culture-making power.

“As someone who thinks through drawing, working between animation and print allows me to use drawing as a way to explore and use duration, movement, and labour in my work in different ways.”

Documentation photo from Diyan Achjadi's year-long series of public artworks, Coming Soon!, 5030-5070 Cambie St, May 2019.

Limitations as Provocations

Printmaking, in particular, offers more than historical resonance or potential as a public work, Diyan says. An element of comradeship is built into printmaking’s nature.

“For one, working in a print shop is always a communal endeavour – there is an ethos of respect, collaboration, and mutual support that I have found in almost all print shops I have worked in, because we must share space and tools and equipment and work alongside each other,” she tells me. “There is always an enthusiasm for sharing our idiosyncratic approaches to making — knowledge sharing is key. Many prints are made in collaboration with a team of people, and in this process there is a respect for each individual’s expertise, skill and contribution.”

Prints, which are typically produced in multiples, are often traded between practitioners, she continues. This likewise encourages community and conversation.

“Discussions about working in the multiple — and by extension, about perceived value, potential distribution, audiences and accessibility — are core to the field.”

The care and patience required to successfully produce prints mirrors the slowing-down those prints aim to encourage in Diyan’s viewers. This effect — a requisite deceleration of frenzied or cursory habits of engagement — also animates Diyan’s practice as an educator. Printmaking, in this way, provides opportunities for development that transcend the pursuit of technical mastery.

“I believe there is a lot to be gained from the experience of working with something that has its own constraints, logics, and demands,” she says. “Not having an ‘undo’ button leads to a slower and more intentional way of working.”

Having to work creatively within material constraints “can also lead one to respond to limitations as provocations or invitations to expand what one thinks is possible,” she continues. “So, for me, the capacity of print in the classroom goes far beyond its potential as a form of communication.”

Documentation photos from Diyan Achjadi's year-long series of public artworks, Coming Soon!, 494 Railway, June 2018-May 2019.

Futurity and Possibility

In April, 2020, Diyan was promoted to full Professorship in the Audain Faculty of Art at Emily Carr University. (She has also held administrative positions including Assistant Dean of Decolonial Methodologies (Foundation) in Culture and Community, which she occupied from August 2017 to December 2020.)

The announcement from ECU’s President’s Office at the time of Diyan’s promotion notes that, aside from her international recognition as “an outstanding artist and expert in her field,” the “depth of Diyan’s engagement in all areas related to teaching cannot be overstated.”

This commitment to the broader work of teaching — the development of the cultural infrastructure within which meaningful learning can take place — was also recently recognized by the Jack and Doris Shadbolt Foundation for the Visual Arts. In April, 2021, Diyan received a VIVA Award, given in recognition of “exemplary achievement by British Columbia artists in mid-career, chosen for outstanding accomplishment and commitment by an independent jury.”

Diyan calls the award an “incredible gift and honour.” But she’s quick to emphasize community as a central feature of her success as well as her stamina; Diyan has been showing work since her first post-BFA show 27 years ago, in 1994.

“I’ve been reflecting with gratitude on how lucky I was as a young

artist to have around me elder queer, feminist, and racialized artists

whose lived experiences modelled for me what a long and sustained

practice could look like, regardless of the dominant culture’s

definitions of what art was supposed to be or what a professional artist

should look like,” she tells me. “They modelled what it meant to be in

community, and the importance of building one’s own networks and support

systems. Their presence and their practices gave me a sense of futurity

and possibility.”

Diyan Achjadi.

In October, Diyan will be exhibiting prints and textiles from the Girl series in Whose Stories?, an upcoming group show at the Kamloops Art Gallery.

Meanwhile, her most recent drawings are “for lack of a better word, fictional islandscapes,” which also include formal experiments with “folds and dimensional structures” within the drawings themselves. They’re still too new to describe in greater detail, she notes. Although for an artist keen to invite questions rather than prescribe solutions, not-quite-understanding-yet is far from an uncomfortable place to be.

“I never quite know what’s on the horizon,” she says.