Exploring Community Through Fermentation and Acts of Micro-Care

Posted on

Artist, writer, designer and ECU MDes student Julie Van Oyen recounts her journey to rethink definitions of ‘self’ and ‘other’ at the 2021 CAGS Symposium.

How can a person care for their community? How can someone be responsible to place?

During the 2021 Canadian Association for Graduate Studies (CAGS) Virtual Symposium, artist, writer, designer and Master of Design student at Emily Carr University Julie Van Oyen proposes these questions as central to her recent thesis work. Answering them, Julie tells the CAGS audience, has involved redefining concepts including ‘community’ and ‘self.’

But this redefinition isn’t merely an academic exercise, she cautions. Confronting our understanding of self and community might be a tool to help address the existential threats we now face.

“There are multiple, stacking and ongoing ecological crises, systems of racialized oppression, white supremacist, colonial systems, and the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic,” she says. “To navigate, transform, survive and take care of each other within these contexts, my research practice engages with questions of how we might remain responsible to place, to our communities and how to enact [this care and responsibility] in real and tangible ways — if only in small ways.”

Fermenting sourdough starter, from Julie Van Oyen's Nested Bodies thesis work.

Recently, Julie’s research has seen her working with microbes in a material practice of fermentation. Relationships between humans and microbial communities are often life-giving for both parties, she notes. In fact, the existence and evolution of human beings as a species are largely dependent on their relationship to microbes. With these ideas in mind, Julie says notions of “what a body is” and “what a community is” can be “expanded.”

A body is not so much a self-contained human organism as it is a “microbial landscape,” and an “interface of myriad forms of life and life-making activities.” Likewise, human communities are inclusive of microbial ones. This “much larger, generational view of community” sees “human-microbial communities [as] nested within each other, entangled in our mutual dependencies for life.”

These expansive perspectives on self and community are partly influenced by the work of Okanagan scholar and educator Jeannette Armstrong, Julie says. In the essay “Sharing One Skin: Okanagan Community,” Jeannette notes that the words for “land” and for “body” share the same root syllable in the Okanagan language.

“This means that the flesh that is our body is pieces of the land,” she writes. “The soil, the water, the air, and all the other life forms contributed parts to be our flesh. We are our land/place.”

Fermenting cabbage, from Julie Van Oyen's Nested Bodies thesis work.

This statement amounts to a declaration of fundamental equity between human beings and other forms of life on earth. It overturns what Julie calls “human exceptionalism and anthropocentrism.” In a sense, it also provides a model for a more personal reckoning with how decolonization can shape a research practice.

In what Julie refers to as the Micro-Care project, a group of eight collaborators — including fellow ECU MDes students Oluwasola Olowo-Ake and Avi Farber — contributed writing and visual content to an open digital publication. The work explored how the group might care in small ways for one another during times of global crises. Because of the equity inherent to this collaborative process, the work actually enacted the care the group sought to imagine.

“We built a community of care and kinship through the development of the work during the COVID-19 crisis — actually in the onset, when we were all kind of in limbo — implicating ourselves into relationships of mutual responsibility with each other,” Julie says.

As the project developed, however, cracks began to show. In summer 2020, a paper about the Micro-Care project was accepted for presentation at an international design conference. The paper had been written by a smaller, core group of contributors, all of whom were white, Julie notes.

Front cover of the Micro-Care publication.

As is often the case, the design conference asked the group to make revisions before presentation. At that time, a collaborator from the larger Micro-Care project, Jacquie Shaw, reviewed the paper, saying it was “pretty clear that the paper had failed to represent how truly intersectional the perspectives were” in the original collaboration, recounts Julie.

To address this gap, a Q and A with Jackie was added to the paper as part of the revision process. Jacquie’s critique was presented as a subsection of the presentation paper, to “show what happened, and the harms that were done,” Julie says.

In their statement, Jacquie points to formalized academic and institutional settings as ones that often reproduce systems of exclusion, bias and discrimination, rather than making space for difference.

“I’m interested in breaking the format of, ‘This is a finished project. This is what we did,’” Jacquie said. “I’m interested in how we can build and share skills around intersectional analysis and intentional intersectional approaches. How do we make those more explicit? … The decolonizing of design keeps coming up. How can we actually practice that while responding to these kinds of calls within institutional settings, which may be at the same time upholding systemic barriers rather than dismantling them?”

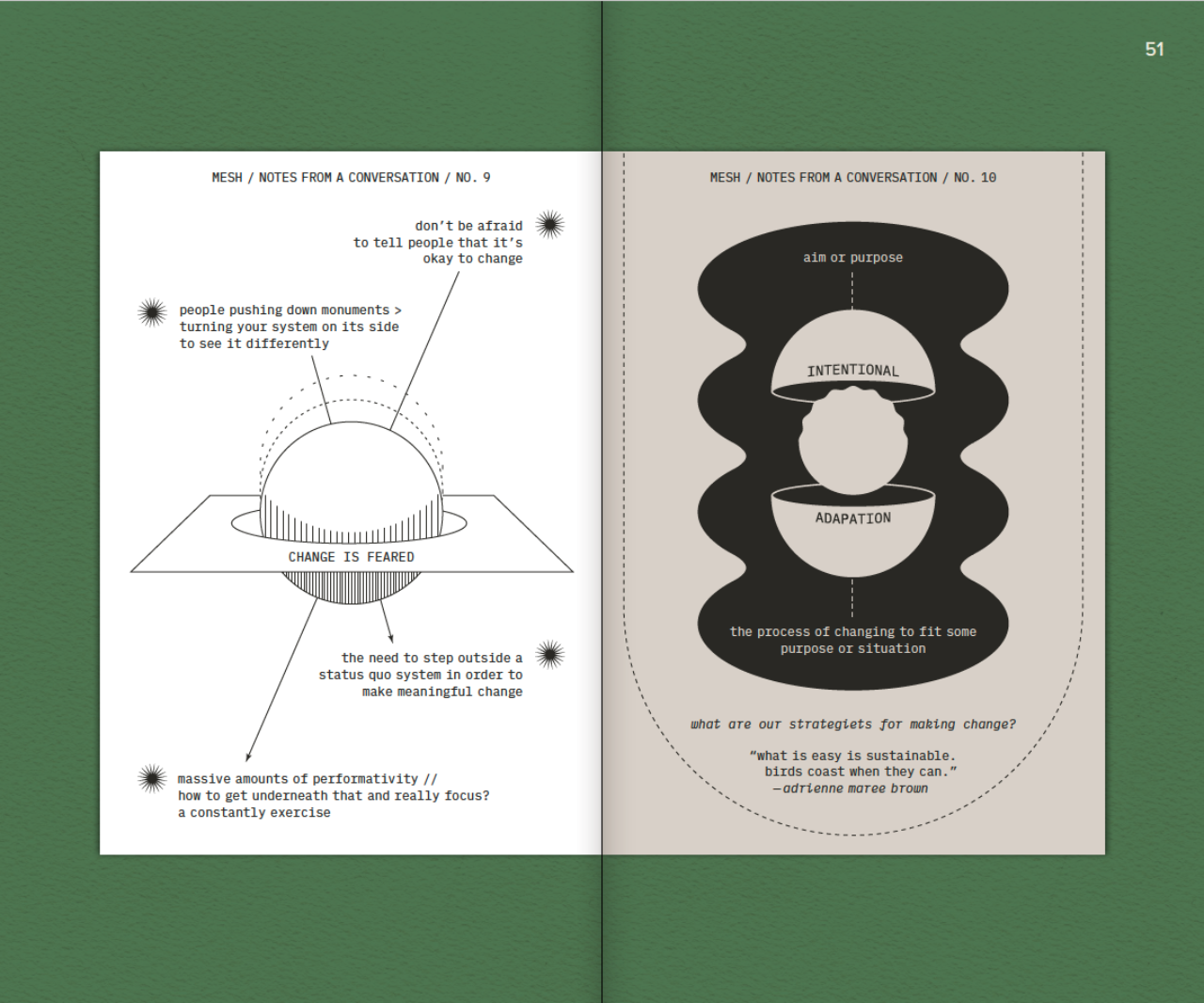

From the Micro-Care project.

These questions continue to serve as a lodestar for Julie’s work, she says. Her interest lies increasingly in “making thicker and messier conversations and keeping everyone in it, even people who are creating the work or doing the research.”

It also lies in “staying with the trouble,” Julie says, referencing Donna Haraway. The more personally a person can situate themselves in their research, the more accountable to its impacts that person will be, Julie says. Implicating oneself in one’s work also opens the possibility for design to impact not only the object of design, but the designer themselves.

“In my work, the ongoing cycles of maintenance and care required to keep the ferments I work with alive have resulted in a deep personal connection and obligation to them, positioning them as co-creators in the work (as opposed to inanimate substrates I work with solely for my own benefit),” Julie says. “I think it’s so important to implicate ourselves … because it keeps us responsible to each other. And it requires us to bring who we are to the process, and acknowledge who we are and what our positionality is.”

You can learn more about Julie’s ongoing fermentation project, Nested Bodies, on the ECU gradshow website. View the Micro-Care document in Libby Leshgold Gallery’s Publishing the Present archive. Visit jvanoyen.com to see more of Julie’s work.