Xwalacktun’s Art is a Call to Find Balance

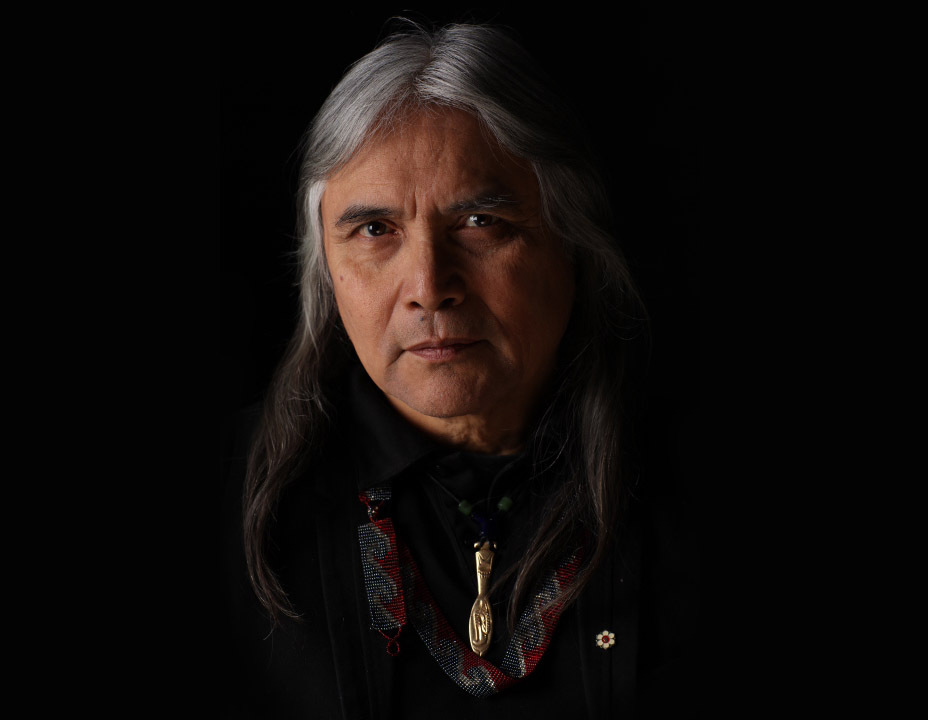

Artist, educator and 2022 Honorary Degree recipient Xwalacktun. (Photo courtesy Xwalacktun)

Posted on

The accomplished artist and educator is a 2022 recipient of an Emily Carr University Honorary Degree.

Xwalacktun, also known as Rick Harry, believes that art was gifted to him at a young age by the creator. With ancestry from Skwxwú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation) and Kwakwakw’wakw Nation (in Alert Bay), Xwalacktun mastered his skills and education with the help of Emily Carr and Capilano University but credits his creativity as a gift from the natural world.

“My art just comes together. With nature, with the ancestors, with community, within my own self, you know, it kind of emerges out of that,” he tells me “I want to give it life. It’s not just a nice piece of artwork to me. We never had a word for artwork. It was the way of our life. It had to blossom out of us to tell a story—a story to help myself or others around me, or the ones that are not here yet.”

That credo guides his practice, which locates its apex in a tradition of reciprocity. This tradition emphasizes a need to protect the natural landscape and its inhabitants for the seven generations ahead of us.

Yet Xwalacktun is mindful he still has to participate according to society’s rules in order to survive. For instance, it’s sometimes necessary to drive a truck to move trees for his practice. Still, he assures me he demonstrates respect and gratitude with each tree through ceremony —he brushes, cleans, and takes a moment to put a prayer over it, promising he will give it new life.

“I breathe it. I breathe in nature. I breathe within myself,” he says. “I pay attention to my surroundings, and I think about the ancestors. I believe that, at times, it’s like the ancestors are coming through, helping me along the way.”.

Xwalacktun at work on a house post in the Aboriginal Gathering Place at ECU. (Photo by/courtesy Connie Watts)

He embodies this relationship by creating a body of work that honours the teachings of slowing down, paying attention to small moments and details, and taking only what we need so that we can leave the rest for others. His art (and the art of many Indigenous artists) is a call to find balance again so that we can all survive and live in harmony. It isn’t just about environmentalism. It’s about life itself. Paraphrasing Chief Seattle, he says, “The earth does not belong to us. We belong to the earth.”

Xwalacktun is keenly aware that he is community-made. He credits his success to the help of many people throughout his life —family, friends, teachers, administrators, and colleagues. “We get people to get involved so they can help bring a story to life,” he says while sharing the details of a current project he’s working on. When I ask him when it will be ready for viewing, he says in a style reminiscent of my own Indigenous elders, “It comes out when we raise it.”

Known for his contributions locally and across the globe, Xwalacktun’s works span over 40 years and various mediums. His practice includes public art, sculpture, metalwork, jewelry, glasswork, drawing, printmaking and, of course, what he is known best for, wood carving. His focus is mainly on traditional Coast Salish design elements, but he has also worked with contemporary concepts and materials.

It would do him a disservice to try to list a lifetime of work here. But you can find many of his works on top of mountains, in parks, at schools, in museums and within communities, such as the totem poles throughout Scotland that symbolize the friendship between Europe and Canada. He has also received numerous awards including The Georgie Award (2002), F.A.N.S Award (2005), Order of British Columbia (2012), Queens Diamond Jubilee Award (2013), Arthur G. Hayden Medal (2014), and The B.C. Achievement Award (2016).

Perhaps one of Xwalacktun’s greatest gifts is the gift of teaching. He has taught and continues to mentor many in Coast Salish design. His voice reverberates with enthusiasm whenever he talks about sharing knowledge and working in collaboration with others.

The seeds of creativity he witnesses in youth and new artists are a testament to the world that inspires him to create every day, advising artists to “do the best they can and then do it better the next day.”

Xwalacktun works on a house post in the Aboriginal Gathering Place at ECU with students Aaron Rice, Jessey Tustin and Randall Bear Barnetson in 2021. (Photo by/courtesy Connie Watts)

Xwalacktun remembers drumming at Emily Carr’s graduation ceremonies. He would sit in front of the stage with everyone and watch people receive their degrees, always feeling immense pride for them. When Emily Carr offered him an honorary degree, it caught him by surprise. His humour seeps through when he tells me how, when invited to the President’s Office to talk, “I thought … I did something bad, and she said, no, it’s not bad.” He laughs, “I was honoured.”

His hope for the future is a world where we have a future at all – one where we know our children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren will have a place to survive and continue this cycle of life.

Xwalacktun thinks back on when he was growing up, watching his father observe the world around him and ask these same questions. He feels sure that this future world was also his father’s dream, a dream, just like the Seventh Generation Principle, passed down across generations.

“We’re all on the same vessel we call Mother Earth which will take us on our life journey.”