Bonne Zabolotney’s Vision for a More Ethical Design Practice

Designer and ECU faculty member Bonne Zabolotney. (Image courtesy Bonne Zabolotney)

Posted on

On the occasion of her promotion to full professor, the designer and ECU faculty member reflects on how to bring ethical perspectives to the work of design.

Throughout much of its history, the world of design has advocated for “universal” and “objective” solutions to problems, ECU faculty member Bonne Zabolotney tells me. But these concepts are a fallacy, she says.

Worse, universal solutions risk ignoring and excluding whole swaths of human experience. Asking “universal according to whom?” is a good way to reveal the bias behind these terms, she notes.

In other words, “universal solutions” paradoxically result in a world that reflects and empowers the experiences of fewer people.

So, what happens when we put aside the question of how to solve a problem more efficiently and instead ask what kinds of worlds are being built by design?

One practice that attempts to answer these questions is known as “axiological design.” The word “axiology” refers to the study of value, she tells me. Axiological design takes value into account. But not only financial value. It places cultural values, personal values and ethics at the heart of the practice of design.

“I am truly interested in this axiological designing, which means what we value, what we find ethical, what is embedded with integrity should reflect back on us,” she says. “It means we should keep growing the integrity of those values and those ethics.”

This philosophy animates Bonne’s practice as a designer, author, editor and educator. It is evident in the BCcampus-funded ‘Co-designing with Anti-oppressive Action Frameworks for Curriculum and Pedagogy’ initiative, which Bonne co-authored with designer and ECU faculty member Cam Neat. It’s central to her forthcoming book, ‘Designing Knowledge: Emerging Perspectives in Design Studies Practices,’ which looks at “how knowledge creation can contribute to an expanded and more inclusive design practice.” And it’s a vital part of her work as a teacher.

Following her promotion to full professor in 2022, I met with Bonne via video chat to find out more.

SEEKING KNOWLEDGE IN GOOD FAITH

In 2020, many longtime advocates for social justice gained mainstream attention for their critiques of how institutions and individuals perpetuate racist structures and policies.

Bonne had long been a follower of a number of these advocates, including researcher and designer Sasha Costanza-Chock. Sasha’s book, ‘Design Justice,’ explores “an approach to design that is led by marginalized communities and that aims explicitly to challenge, rather than reproduce, structural inequalities.”

On Twitter, Sasha asked in 2021 for recommendations on a PhD design program that had an anti-oppression framework.

“I thought, well, yeah, we can do that. We’re equipped to do that,” Bonne recounts. But there was no reason to restrict it to a PhD program, she thought.

“In design, if we’re seeking knowledge in good faith, then why wouldn’t we work on something like this? And why wouldn’t we share this with our community? Why wouldn’t we make it open access, open education, and try to move forward with that?”

Working with ECU design faculty, Bonne and Cam led the creation of the ‘Co-designing with Anti-oppressive Action Frameworks for Curriculum and Pedagogy.’ They worked with ECU design faculty members throughout 2021 and 2022 to “co-design” the document. Designer and educator Ramon Tejada also contributed.

Co-designing is a way to ensure projects grow “from the ground up,” Bonne adds. “That way, no one needs to ‘buy in’ because they already see parts of themselves reflected in the work. They recognize their contribution to it. And that really is like joint ownership.”

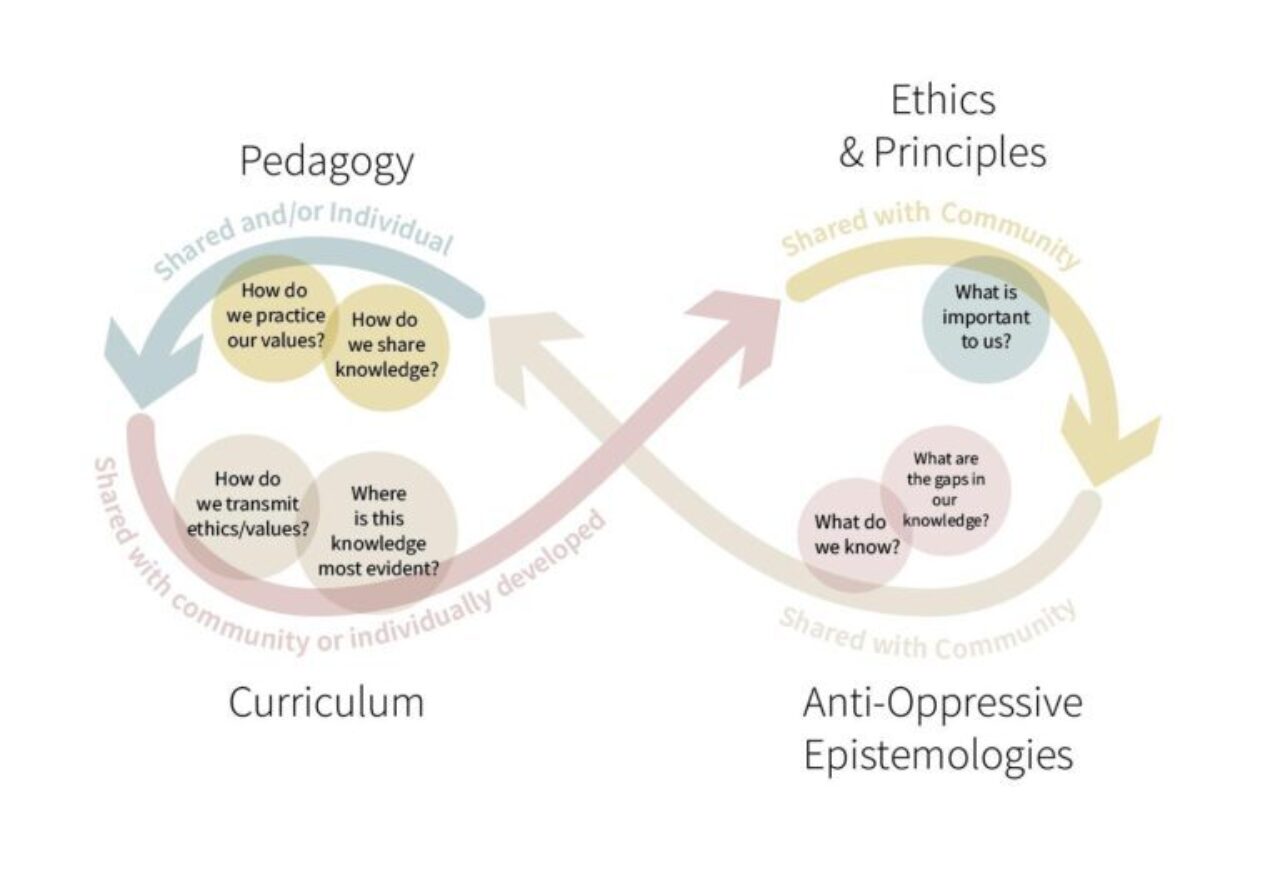

Launched in 2022, the frameworks are “a tool that assists in sharing knowledge from marginalized sources and challenges designers to rethink how their pedagogy and curriculum might reproduce inequalities.” Bonne says she looks forward to working on ways to embed its principles more concretely in ECU’s design programs.

WHAT DESIGNERS UNDERSTAND

As with the frameworks, Bonne tapped fellow designers to contribute to her forthcoming book, ‘Designing Knowledge.’

The book explores a discipline known as “design studies.” Design studies examines the knowledge designers bring to bear on their own field. But design studies is a field often led by people who have no background in design, Bonne notes.

“It isn’t often that designers themselves would have a voice within design studies,” she tells me. “So, this book is about expanding the field of design studies. It’s about what designers understand and know about design as we design.”

Ironically, the peer-review process brought pushback from American colleagues. The book’s expansive vision rattled scholars who felt opposed to change.

“We have networks of legitimization set up in our fields that tell us what’s acceptable and what is not,” she tells me. “When you start to break the rules, you run the risk of not being accepted or not being published. Of not being seen. Because you’ve got gatekeepers rather than colleagues.”

Fortunately, the book impressed a majority of peer reviewers and is set for release in October.

Bonne wrote several chapters and edited the work. It also includes chapters from designers including ECU faculty members Celeste Martin, Louise St. Pierre, Sophie Gaur, Pat Vera and Leo Vicenti.

“They’ve got amazing information to share,” Bonne says of her co-authors. “I’m so lucky to know such smart people. They write beautifully and I’m excited for other people to be able to see how wonderfully they express their own work.”

From the BCcampus-sponsored ‘Co-designing with Anti-oppressive Action Frameworks for Curriculum and Pedagogy initiative.’

DISCIPLINED SELF-REFLECTION

Even with guidance, bringing an ethical perspective to design is not easy, Bonne says. It requires a great deal of self-searching. But this, she adds, is the point.

“We all have life experience. Doesn’t matter how old you are. We all have tragedies, we have delightful experiences. We have hardships. And all of that comes to bear on the work we do,” she tells me.

Ignoring this reality leads to all kinds of problems, including the idea that universal design is possible. But embracing it will produce work that is more honest and inclusive. It will also lead to work that is more fulfilling.

“Designers for decades were taught to ignore their lived experience. To be objective. And I really encourage students to bring their whole selves into their work. That will always provide meaning. It’ll always contribute meaning to what they do.”

Helping students build confidence in their abilities is one way to advance this goal, Bonne tells me. But centring lived experience is in no way an “anything goes” approach, she adds. It’s a methodical exploration aimed at developing frameworks within which a designer can operate. Establishing such frameworks empowers students to step forward confidently and in good faith to claim their space.

“I want my students to be comfortable enough to say, I’m

not required to be objective. There’s nothing constraining me from being

guided by my own morals and ethics, as long as I can be explicit about

that. Or, I don’t have to be unbiased. I just have to be disciplined in

self-reflection, so that I understand why it is I think, why I am the

way I am or why I’ve made the choices I’ve made.”

KEEP MOVING IN A POSITIVE DIRECTION

Ultimately, Bonne would like to see designers recognized for their ability to expose underlying issues, she tells me. Designers are more than just aesthetes who can make something look good or help a marketing campaign succeed. Designers are skilled investigators who can understand and map out complex systems. They’re natural deep-diggers, with a passion for nuance and detail.

When an ethical framework is used to direct these rare skills, a formidable advocate for change may emerge.

“And then we can move forward. We can talk about complex issues like climate change or political instability or racial inequity. And we can do so in good faith,” she says.

Because it’s really about designing in good faith and saying, ‘I don’t just have intentions. I’m going to try and act upon this. And it may not be perfect, but what it reflects back on me, I will understand and know and grow from that. And I will keep moving in this positive direction.’”

--

Visit ECU online today to learn more about studying Communication Design at Emily Carr.