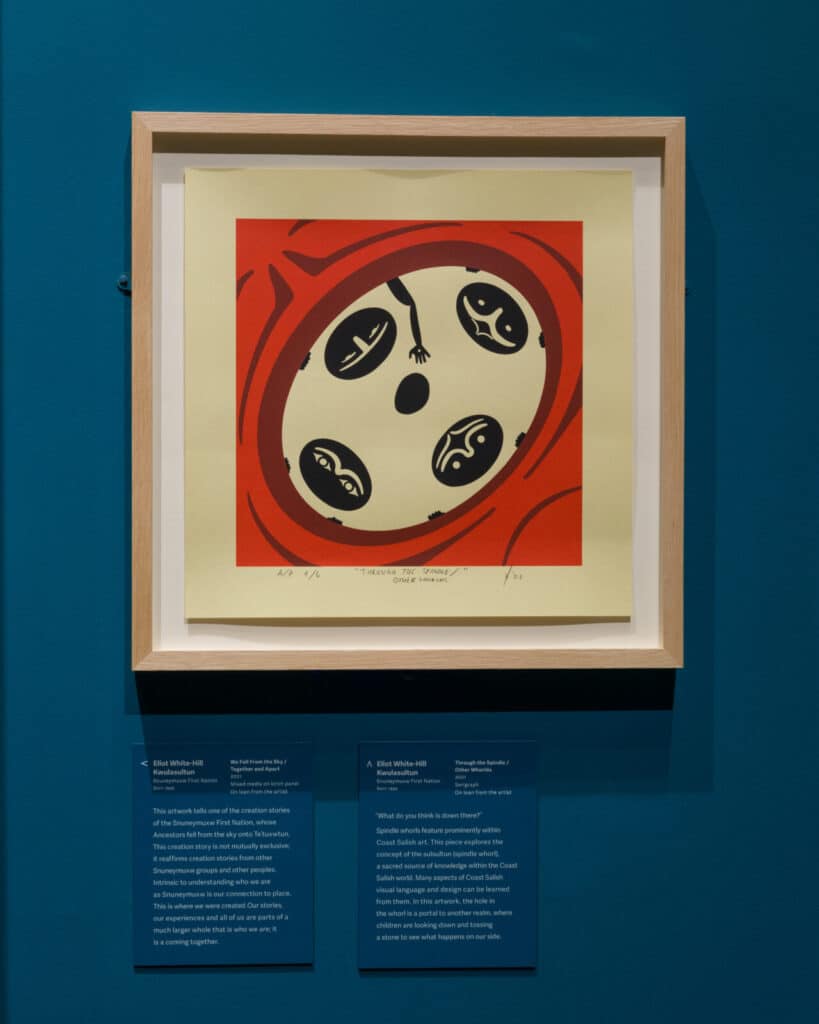

The artist and recent MFA grad is among five artists selected for the museum’s new exhibition celebrating contemporary Northwest Coast Indigenous art.

Artist Eliot White-Hill, Kwulasultun (MFA 2023) is one of five Northwest Coast artists participating in a new exhibition at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City, NY.

Eliot, who is Coast Salish from Snuneymuxw First Nation and also traces his roots to Spune’luxutth and Hupač̓asatḥ First Nations, calls the feeling of showing in the storied museum’s Northwest Coast Hall “surreal.”

“It’s such an honour to have my art on display here, to be asked to be here, to be representing myself and my family and my community in this way,” he says via phone from New York. “It’s also a complicated feeling because the objects in the Northwest Coast Hall, for the most part, did not arrive in New York City in a good way. They should be back home where they belong.”

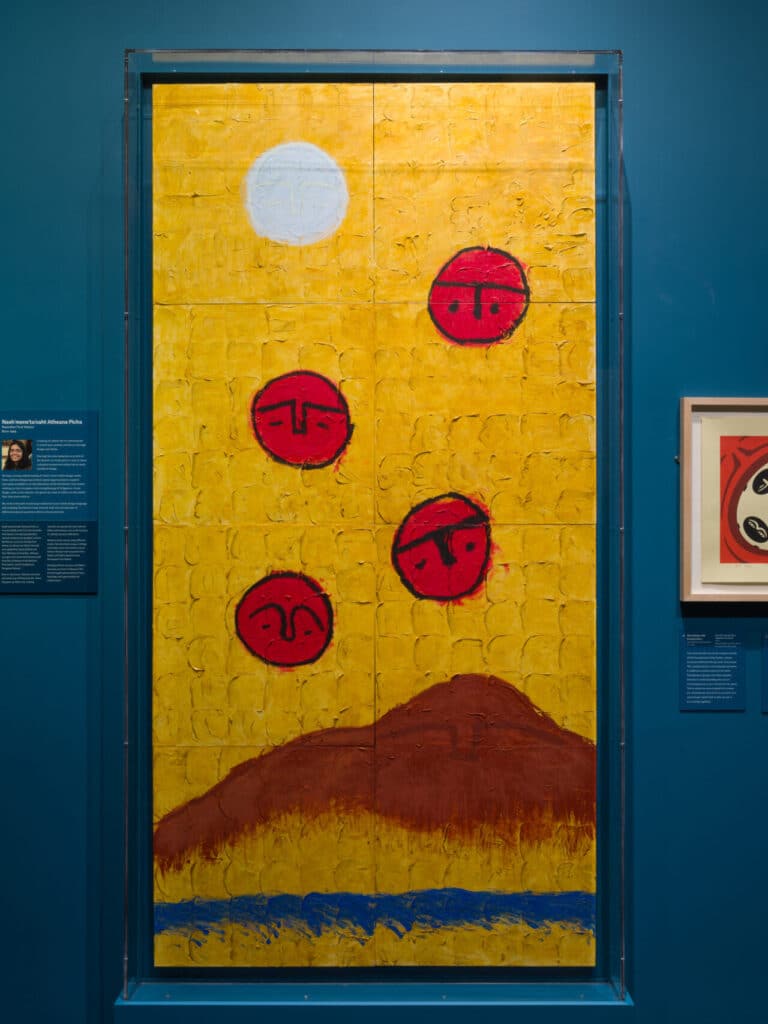

Titled Grounded by Our Roots, the show also features works by Hawilkwalał Rebecca Baker-Grenier (Kwakiuł, Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw, Skwxwú7mesh), Alison Bremner Naxhshagheit (Tlingit), SGidGang.Xaal Shoshannah Greene (Haida) and Nash’mene’ta’naht Atheana Picha (Kwantlen First Nation).

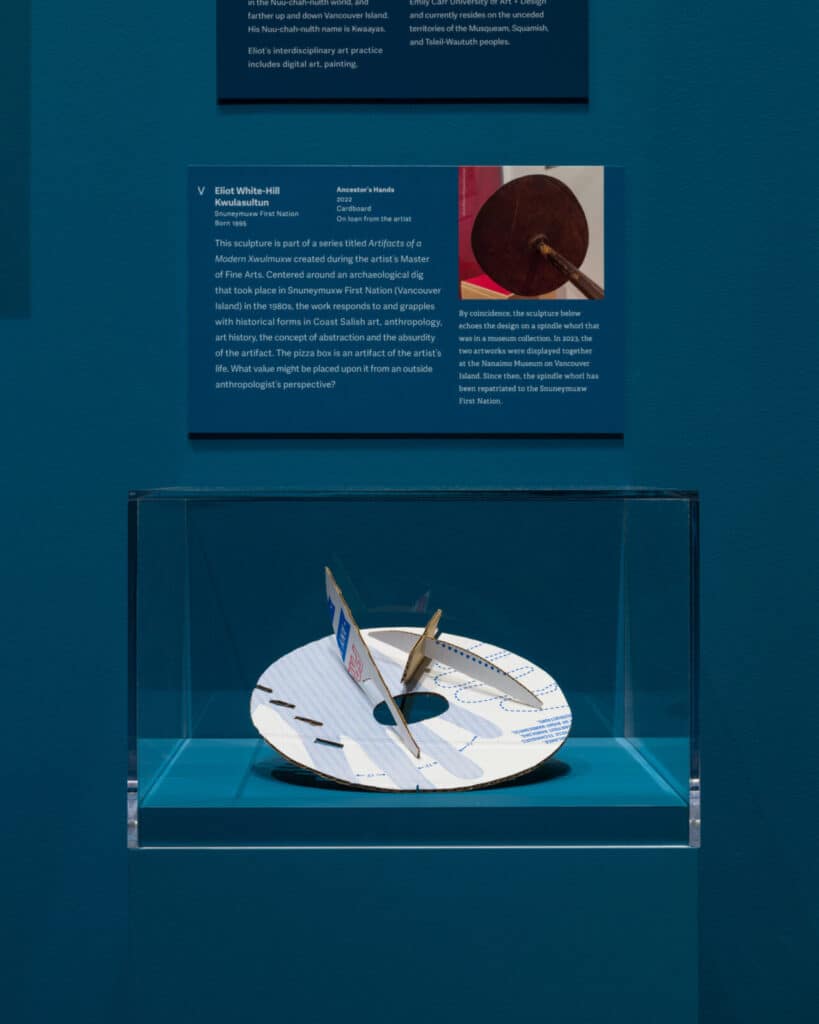

Eliot says he feels honoured to show alongside this group of brilliant artists, some of whom he already knows personally. Shoshannah, for instance, is a close friend with whom Eliot often spends time drawing or watching films in Vancouver. He notes one of his works in the AMNH show was created during his final year in the Emily Carr University MFA program.

Over a few days in New York, Eliot spoke with journalists and attended an opening ceremony with museum board members, staff and other museum associates. He was also able to spend time in the archives, which he says contain one of the world’s most significant collections of Northwest Coast art.

Many of the items in the archive are no longer on public display. New regulations, passed earlier this year under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, require federally funded institutions to obtain permission from Indigenous Nations to display remains and cultural objects. This spurred the AMNH to close two halls dedicated to Indigenous cultures of North America and cover cases containing Indigenous artifacts.

In the archives, Eliot was able to hold a small carving that had been taken from his home community more than a century ago, which he says was both profound and painful. Meanwhile, his work in the Northwest Coast Hall shares space with a pair of potlatch screens that were made by his ancestors on Vancouver Island.

“It’s a complex feeling because they should be in Port Alberni with my family,” he says. “But I hope that my art being there can offer healing to those potlatch screens that have been in New York for over a hundred years now.”

He also notes that museum administration was keen to hear from him and the other artists on how the museum could do better.

“They wanted to hear our views as young and emerging Indigenous artists and knowledge keepers in our own right,” he says. “We shared our perspective. The work of repatriation is very much a political project between the institution and our Nations on a government level. Still, it can be pushed along by individual artists like us, which is, I think, an important thing we can help achieve.”

Sharing his work with the broader public is likewise a meaningful way to advance the work of reflecting the vibrancy and vitality of Indigenous cultures, he says. The museum can see upwards of 25,000 daily visitors walk its halls — more people than live in Port Alberni, BC, where Eliot grew up.

“The museum wanted to bring together a group of up-and-coming Northwest Coast artists who are doing work that is affirmative of our lived experiences and identities within the modern context,” he says. “So it’s really incredible to have been chosen.

“There’s a renaissance of Indigenous art happening, and we’re in a moment where there’s serious public appreciation for Northwest Coast art, both for its aesthetics and for its cultural significance — for the stories and knowledge it carries. We belong on this stage and people want to hear our stories and our voices and see our work. To me, that can’t be overstated.”

Grounded by Our Roots will be on display at the American Museum of Natural History through spring 2025. Eliot will return to the museum in November to give a talk on Coast Salish woolly dogs as part of the AMNH’s SciCafe series.

Visit Eliot’s website and follow him on Instagram to learn more about his work.