House Post Carved by Xwalacktun Nears Completion

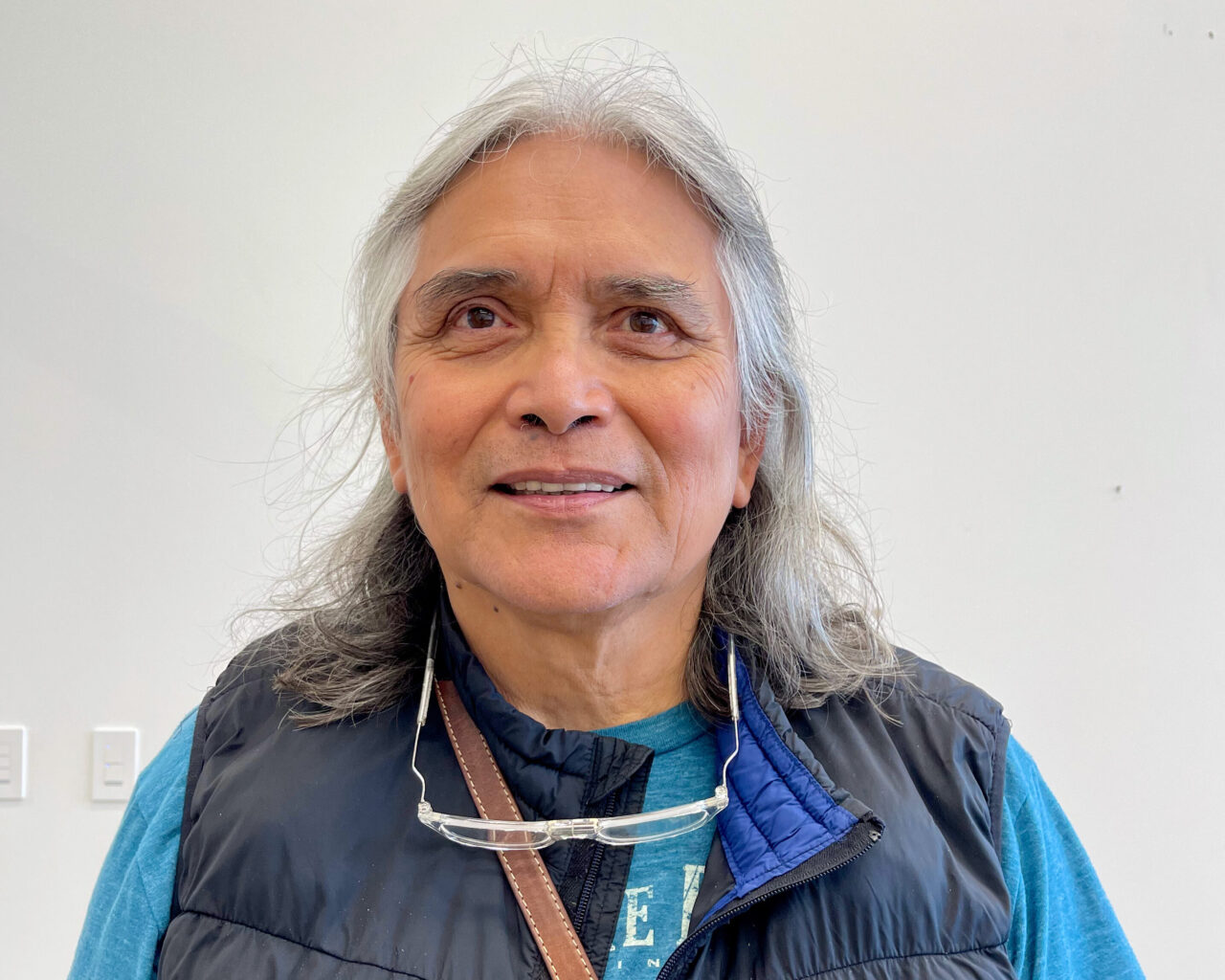

Xwalacktun at work on his house post in the Aboriginal Gathering Place. (Photo by/courtesy Connie Watts)

Posted on | Updated

The master carver and Order of British Columbia recipient has been working on the post for months at the Aboriginal Gathering Place with the help of Indigenous students.

Award-winning artist, educator and master carver Xwalacktun (alumni 1982) was nearing completion on a house post, created in collaboration with Indigenous students at Emily Carr University, when he took a break on a winter Monday to talk about the project.

Xwalacktun, who is of Squamish and Kwakwak’wakw ancestry, has been working on the post in the Aboriginal Gathering Place since the summer. The design, he tells me, pays homage to the work of the late Chief Joe Mathias — a revered carver, activist and community leader, born in the late 19th century.

“My mother reminded me that when she was five years old, she used to look out the window and see him carving in this style,” Xwalacktun says. “She’s going to be 92 this year. So, this is quite a long while ago that this style was being carved. I took Chief Joe Mathias’ forms, his designs, but I did it my own way.”

Traditionally, house posts are structural, Xwalacktun says. They’re installed in a home to hold up a beam, for instance, and are carved with representations of that specific household. In the case of Xwalacktun’s current project, the finished post will eventually be installed on the staircase leading into the north atrium at ECU.

Xwalacktun explains his vision for the house post. (Photo by/courtesy Connie Watts)

As part of his work on the post, Xwalacktun apprenticed three Indigenous students. Other students stopped by at various points, likewise learning technique and history and contributing to the post itself by “taking some wood off,” as he puts it. For Xwalacktun, the role of mentorship is inseparable from the work of an artist — or any other community member with knowledge to share. But using art as a tool to help younger generations feel connected to their history isn’t a new idea, he tells me.

“That was the focus back in the day, too — when things like this were done, they were used as a teaching tool,” he says, adding that western conceptions of “art” don’t quite ring true with how the Coast Salish viewed carving, painting and related forms. “We didn’t have a word for art. It was something we did just like anything else, and there was always a reason for it while we made it. It wasn’t just something we did to make our place look beautiful.”

Looking both to the past and to the future for inspiration has been an important theme for Xwalacktun throughout his career. He traces his focus on Coast Salish-specific design elements in the house post, for instance, to a Sacred Run across Canada in which he participated many years ago. Sacred Run were events started by Ojibwe civil rights leader, teacher and author Dennis Banks and Oglala Lakota civil rights leader, artist and writer Russell Means, both of whom famously helped lead the 1973 protest occupation of Wounded Knee, S.D.

Student Hanna Stewart “takes some wood off.” (Photo by/courtesy Connie Watts)

“While I was on that journey, I saw Charles Elliott’s [T’sartlip First Nation] work, what he had painted on an elementary school,” Xwalacktun recalls. “I stood there and I looked at it and I said, ‘Wow, I need to focus more on Coast Salish design.’”

Having never forgotten that revelation, Xwalacktun points out the many ways his work continues to honour the Coast Salish tradition. The thunderbird at the top of the house post is a nod to Chief Mathias Joe, he says. It’s also used by the Squamish Nation as one of their logos, and is a symbol of “something greater than us,” something connected to the supernatural, he adds.

The four feathers are from an eagle. The number four represents the seasons, the cardinal directions, the elements and the lifeline (infant, youth, adult, elder), he tells me. The eagle feather itself, meanwhile, is an important and powerful symbol, indicating a creature that is closer to the creator than humans.

“If an eagle was soaring above us in a circle, our belief was, ‘Wow, we raise our hands. Give thanks. Because it’s creating this invisible eye for us to say something to the creator,’” Xwalacktun says.

Xwalacktun works on the house post with students Aaron Rice, Jessey Tustin and Randall Barnetson in 2021. (Photo by/courtesy Connie Watts)

Beneath the thunderbird, the bear figure represents power, strength, nurturing and caring for the family. The crescents, meanwhile, represent mind, body and spirit, while the Salish eye symbolizes looking into the spirit world.

“A lot of Salish design is meant to remind us that we’re always being watched by the creator, ancestors, community, family, friends, our consciousness, ourselves,” he continues.

“When I first came out of art school myself, I was making awesome work, but it didn’t have a backbone to it. Later on, when I changed my way of life, I started to focus on, ‘What is the reason why I’m really doing this?’ I realized there’s a lot more work to be done other than just what you see in the physical work. I have to also work on myself.”

In other words, working on a practice is working on the self, he tells me. And committing to that work can help others, too.

Xwalacktun in the AGP. (Photo by/courtesy Connie Watts)

Xwalacktun also made a point of acknowledging how the house post project is one way the university has worked at following the calls of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The work of rebuilding what was destroyed by colonization will take a long time, he says. But remaining committed to that rebuilding is crucial for the creation of an equitable future.

“It might take 150 years to rebuild it, but we have to continue doing it,” he says. “So, we raise our hands to the university for their work, and for taking on this project also. We’re all in the same canoe, we always say. Mother Earth takes us on our life journey. We all have to work together, pull together, look after what we share, look after the earth so that the generations coming after us have something left.”

You can learn more about Xwalacktun’s practice on his website.

Visit the AGP online today to find out about their extraordinary range of programming and resources.