The celebrated multidisciplinary artist and 2024 Emily Award recipient reflects on the relationship between art, meaning-making and perennial openness.

Nadia Myre is at home in Montréal between trips abroad, and the city is buried under snow.

The award-winning, multidisciplinary artist, whose past decade has seen her participate in well over 100 shows, more than 25 of which have been solo exhibitions, is enjoying the soft reprieve granted to her city — and perhaps herself — by the early spring snowfall.

“It’s really awesome,” she says.

Nadia is currently preparing to return to France where she’s conducting a residency at Le Centre International d’Art et du Paysage. A solo exhibition at the centre will follow in the summer.

Known for her longtime exploration of themes including identity, language, longing and loss, Nadia’s work often makes reference to her Indigeneity (she is an Algonquin member of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation).

But her inquiry into nationhood and the politics of belonging is far from strictly personal. Through its expansive conceptual purview and a seemingly intuitive sensitivity to material languages, Nadia draws lines between her own lived experience, the process of collective meaning-making and the possibility of collective healing.

She notes this can be complicated in a country like France, where post-colonial discourse has yet to penetrate many mainstream conversations.

“I sometimes struggle with how to always question my relationship to a place; why am I here talking about my work? What’s the connection with my work to this place?” she says of such experiences.

“And then sometimes more lately, I’ve given myself permission to not necessarily have to always be digging so deep. The world is really, really intimately connected, and the histories are connected. There’s a link and there’s a tie, and there’s a commonality of experience. And I do think it’s of value to do international exhibitions and participate on an international stage in that regard.”

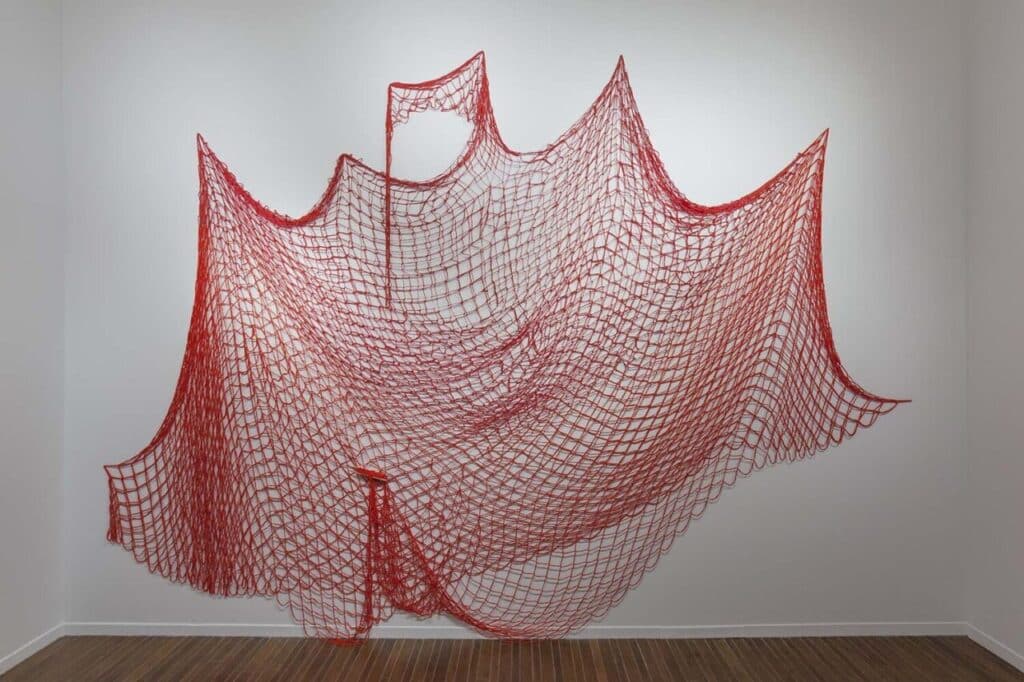

To her credit, Nadia has consistently found thoughtful, evocative ways to foreground these interconnections. Her work Traverser l’Océan / Across the Ocean, created in 2014 for the exhibition Formes et Paroles on Gorée Island in Senegal as part of the 15th Summit of La Francophonie, was made in part using traditional fishing-net techniques. She first began learning the skill during a residency in Québec organized by Sonia Robertson, then later from fishermen in Mexico while working on a land-art piece for the Cumbre Tajín festival, and again from local fisherman in Senegal during the making of the work itself. In doing so, Nadia surfaces a material history that connects distant cultures.

Across the Ocean also makes explicit reference to an 18th-century Black enslaved woman in Montréal known as Marie-Joseph Angélique. Marie-Joseph’s story provided an opportunity to “explore Montréal’s slave history and share it with the people of Gorée, metaphorically bringing a story ‘from the New World’ home,” Nadia said in 2014.

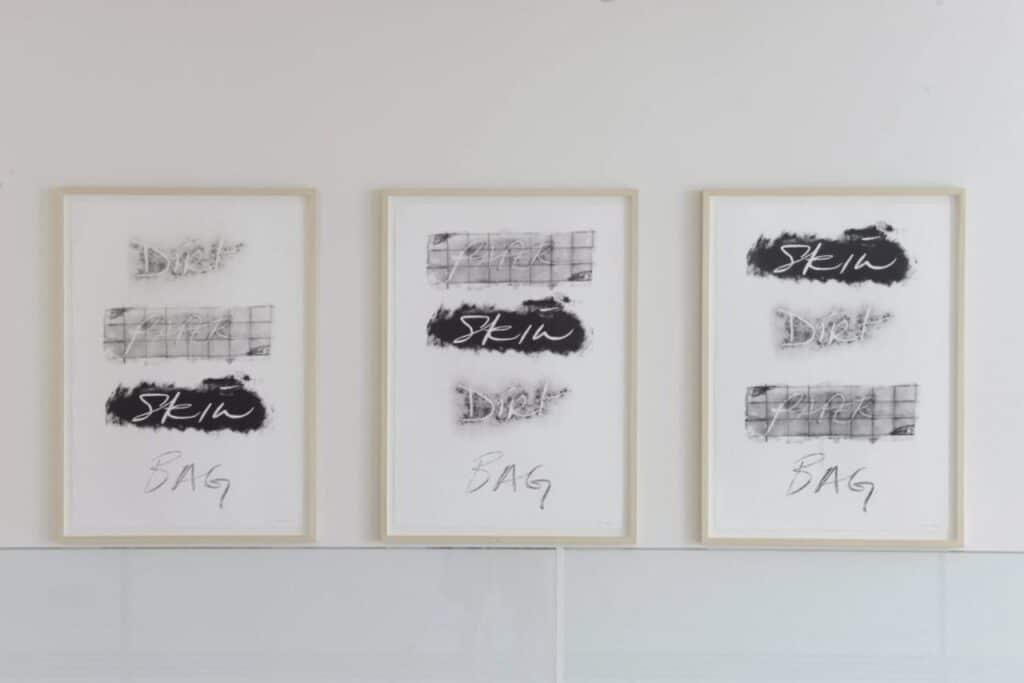

(Top + bottom): From Nadia Myre’s Tell me of your boats and your waters, where do they come from, where do they go? 2022. Installation view at Gallery 2 of Edinburgh Printmakers. Commissioned by Edinburgh Art Festival. (Photos courtesy Nadia Myre)

This characteristic depth and humanity have earned Nadia a string of honours including the Sobey Art Award, the Ordre des arts et des lettres du Québec Cultural Ambassador Award, the inaugural Walter Philips Gallery video award from the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and the Pratt & Whitney Canada and Conseil des arts de Montréal: Prix les Elles de l’art.

Her work is held in collections belonging to museums, governments and corporations. She has won public art commissions across Canada and abroad. She is the recipient of nearly two dozen grants including several from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. And she has a long history of curatorial and community engagement, including as co-founder of daphne, Québec’s first Indigenous artist-run centre.

As of 2024, she is also the recipient of the Emily Award from Emily Carr University, which recognizes the outstanding achievements of ECU’s alumni community.

But Nadia says the career she’s built over the past quarter-century since graduating from Emily Carr was far from a sure thing.

“I was interested in getting an education in art not because I had a conviction that I was going to be an artist, but rather I was interested in understanding the world differently,” she says.

Even after completing her MFA at Concordia in 2002, she considered pursuing disciplines including writing and architecture.

“Circumstance and opportunity changed that for me,” she says, noting it’s the unforeseeable that so often helps a life take shape. But a career as a professional artist also requires a degree of fortitude that can be hard-won if not entirely out of reach for many aspiring practitioners, she adds.

“It requires a faith in the universe that is uncomfortable, and a lot of people don’t have the tenacity for that,” she says. “But that doesn’t matter, right? Because what you’re learning in art school opens your mind to the world. And the tools you get through your education allow you to be adaptable and flexible and courageous, in a way.”

Nadia’s own faith in the universe was tested early when, in 1997, during her final year at Emily Carr, she was accused of racism by a fellow student who took exception to an artwork she displayed in a campus gallery. The issue divided the school, spurring public forums from which Nadia herself was conspicuously absent. She notes the controversy effectively ended her participation in her final year of studies. She graduated on the strength of her acceptance to Concordia’s MFA program, and by making up missing credits during a summer semester.

Looking back, Nadia says the issue was driven by overreaction and misunderstanding. But she also acknowledges the ways the experience influenced her approach to art-making.

“I can see how this event shaped my practice; to make work that was more under-the-surface,” she says. “To not spit out what I was thinking.”

She adds that this lesson stood her in good stead as she began to develop the themes that animate her practice today, though it would be years before she found a community of like-minded practitioners. The conversation around colonization was, at that time, far from prepared for an encounter with her exploration of Indigenous identity, she says. ECU, for instance, only hired its first Indigenous representative in the years following Nadia’s graduation.

But Nadia says the issue was no less complex for her personally.

“At the time, I was struggling with my own relationship to an Indigenous identity that, in a way, was new,” she says. Her mother, an orphan, wouldn’t reestablish contact with her Nation until later in life. Neither she nor Nadia grew up on reserve or with their Nation’s language. Nadia only obtained status in 1997, the year she left Emily Carr.

“The work I was doing was really trying to understand what it means for me to be this person who speaks English and French and has this education and on the outside seems pretty assimilated and white. What does it mean to be Indigenous, having never really grown up in the culture, with the language, on the land? I guess that’s the primary question that drives the work.”

Arguably, this type of complexity also endows her work with its broader resonance.

Understanding how to contend with such complexity came from finally discovering “there were others out there like me. And that my search was, in a way, legitimate.” Meeting and encountering the work of artists such as Dana Claxton, James Luna, Rebecca Belmore, Greg A. Hill and David Garneau proved to be revelatory. The process of having moved through a place of uncertainty to one of equilibrium and interconnection has defined Nadia’s artistic trajectory ever since.

“One of the things I’ve always been motivated by is learning. I never want to put myself in a situation where I think I know what I’m doing,” she says. “It becomes a challenge of understanding how you are leaving your voice in a particular process. But if I’m guided by learning, then I’m always excited about a project.”

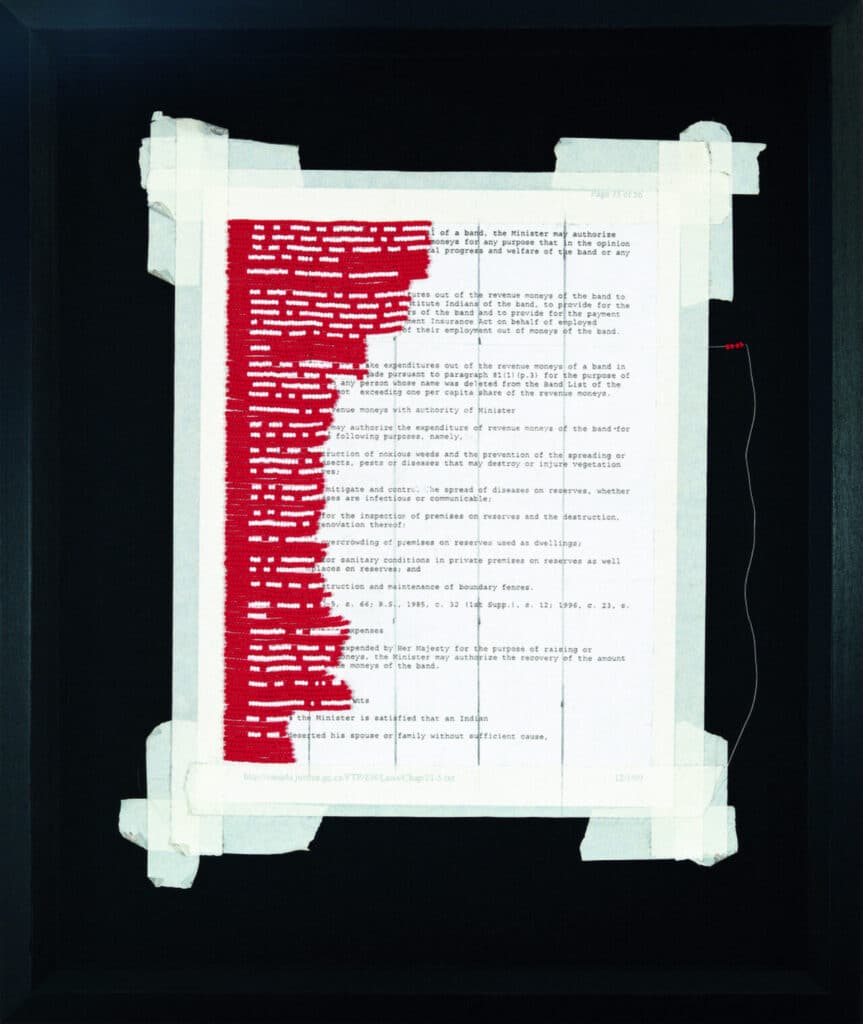

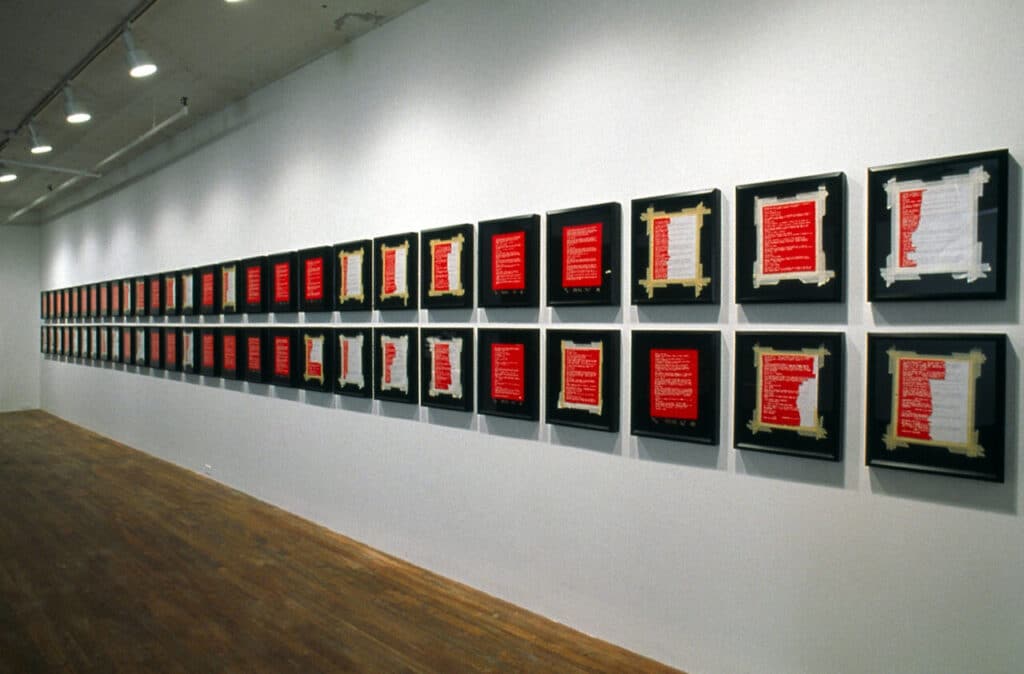

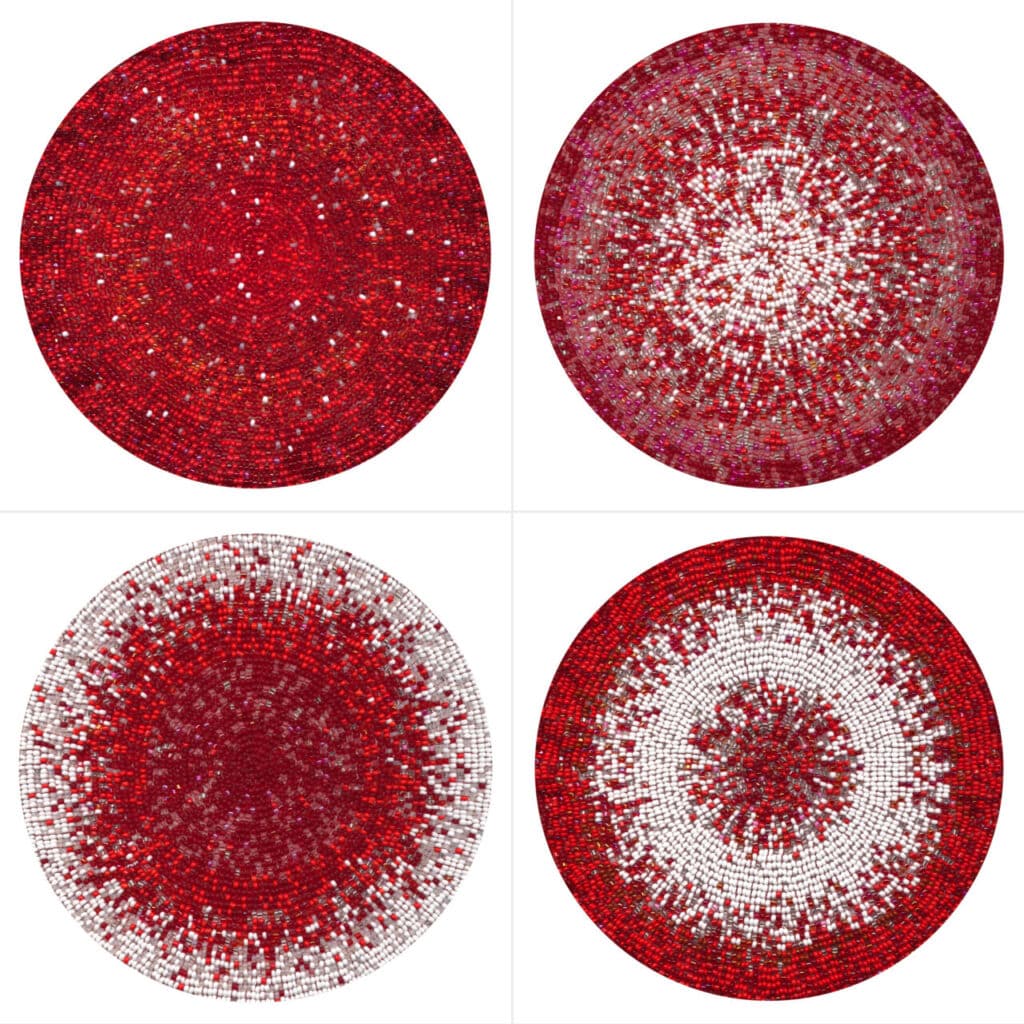

Nadia’s considered engagement with specific mediums and processes bears evidence of this perennial openness. Her works Indian Act and Meditations, for instance, both employ beadwork. But they follow different sets of “rules,” she notes. The former, which was produced with contributions from more than 230 friends, colleagues and strangers, uses beads to trace every word and space of the Government of Canada’s 56-page Indian Act, engaging metaphorically and directly with the legislation that governs Indigenous status, First Nations governments and the management of reserve land and communal monies in the country. The latter tracks drops of blood, bead by bead, to question the notion of hybrid identity, and appeared as large-scale photographs on billboards in nearly every province and territory in Canada.

Both works are premised on a question — one about sovereignty, the other about personhood. And both use a formal device to mark Nadia’s engagement with these questions, which are at once personal and existential. But both works also exhibit a profound aesthetic sensitivity, suffused, as they are, with what one might be forgiven for calling real beauty. According to Nadia, this is by no means an accident.

“I think some of the best art sometimes really moves you through affect,” she says. And while a pursuit of affect can be a slippery one, its success often relies on preserving space for not-knowing. “It’s important for me to develop ways of working that allow for mystery to embed in the practice.”

n essence, Nadia is describing a kind of quest for reciprocity — with the world, with its histories and with the works themselves. She notes she aims to “allow space for other information to come back through the making of work.”

It occurs to me, at this point, that I can see some of what generates the genuine warmth, good humour and resolute groundedness with which Nadia has conducted our conversation. She laughs a little when she says that she finds the notion of constantly exerting one’s will “incredibly boring.” Though she adds that “some people do it really well and they’re very successful. Maybe mine was the harder path. I don’t know.”

She pauses, giving some thought to where her reflection might lead.

“Sometimes, exerting your will can be necessary, especially when it’s in service to a vision,” she continues. “But I believe that if the thing is supposed to be, then it happens, and it happens in the way it’s supposed to happen. And all of that is information. It’s about seeking, really.”

Want more stories like this one delivered twice a month to your inbox?

Subscribe to our free Emix newsletter today!