Place-Based Making Connects Industrial Design Students with Living Histories of Local Materials

Third-year Industrial Design student Nabi Park receives guidance from ECU faculty member Heather Young during a workshop led by Musqueam artist and cedar weaver Rita Point Kompst at the Aboriginal Gathering Place at ECU. (Photo by Perrin Grauer)

Posted on | Updated

In a third-year class led by ECU faculty member Heather Young, students were challenged to develop sustainable, ethical and culturally appropriate design practices.

A core third-year Industrial Design course at Emily Carr University of Art + Design (ECU) teaches students to search no further than their own backyards to find materials and techniques with rich social, ecological and cultural histories.

Led by designer and ECU faculty member Heather Young, the class explores “place-based making,” an approach that emphasizes an enduring sensitivity to local contexts, including community and place.

“I tell the students, yes, we are designers, but rather than relying solely on your training and expertise to guide you, you are centring the land and materials,” Heather says.

“I talk with them about our responsibilities as human beings and about reciprocity. We talk about techniques which may require more labour, but are less harmful to the earth. And I ask them to consider how they might open their practice to these ideas moving forward.”

Top: Cedar materials are laid out on a table during a basket-weaving workshop led by Musqueam artist and cedar weaver Rita Point Kompst in the Aboriginal Gathering Place at ECU. | Bottom: Alex Turnbull works on a woven cedar basket. (Photos by Perrin Grauer)

Heather notes place-based making involves a great deal of research, critical self-reflection and careful consideration of the impacts — intended or otherwise— of any project. In the context of her third-year class, students were tasked with designing a vessel using only materials that were foraged or found and might otherwise be considered waste.

To begin, students mapped their neighbourhoods and identified any plants they encountered. Then, they compared their maps with records showing the locations of traditional Indigenous territories and settlements. They identified which languages are spoken and the Indigenous names for plants and places.

Doing so underscored the cultural and political significance of the materials they encountered, Heather says. This is not only an exercise in ethical practice but an opportunity to discover ways of working that align with and address a person’s values, preoccupations and concerns.

In an early spring workshop at the Aboriginal Gathering Place (AGP) at ECU, students gathered to learn from Musqueam artist and cedar weaver Rita Point Kompst about a Coast Salish approach to harvesting, preparing and working with cedar. Rita spoke about the history of the practice, as well as methods for ethical and sustainable harvest.

She also told students how these methods reflect the broader scope of Musqueam science, philosophy and cosmology. Heather says practices like Rita’s are so powerful precisely because of how they connect physical and material making to ethical and existential frameworks.

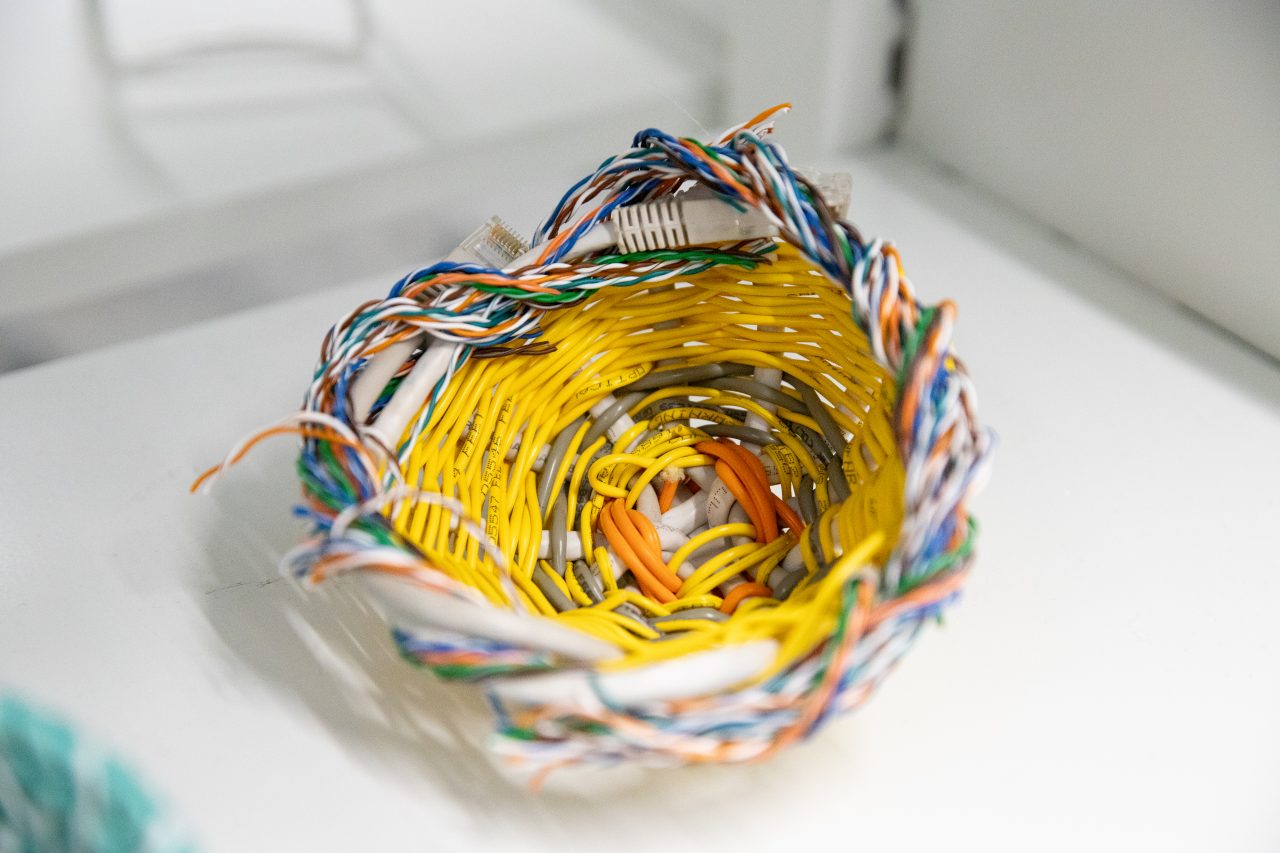

Weaving a series of vessels from found and salvaged electrical cables, third-year student Alex Turnbull discovered their relative heaviness meant the vessels collapsed under their own weight once the structure grew past a certain size. Vessels seen here in display at ECU Library. (Photos by Perrin Grauer)

For students, the curriculum has proven both challenging and rewarding. Third-year student Alex Turnbull says her previous classwork focused on more traditional industrial design approaches. She notes Heather’s course required a major shift in thinking.

“It was weird for me, and I think many of us were finding we had to let go of our impulse to control things,” she says. “A lot of people, me included, would sit down with the brief we were given and immediately draw what we wanted our outcome to look like. But since our materials are so unruly, things wouldn’t happen as planned.”

Alex used found and salvaged electrical cables to weave a series of vessels. She notes their relative heaviness meant the vessels collapsed under their own weight once the structure grew past a certain size. She recalls being frustrated that the cables wouldn’t perform as she’d envisioned. But then a friend told her, “Maybe that’s just the way the wires are.”

“I realized, right, we’re supposed to let the materials do what they want and embrace that and let it show,” Alex says. “If that had happened in a different class, I would’ve fought to make my materials do what I wanted. But Heather was pushing us toward spaces we weren’t quite comfortable with, and it led me to understand the materials in a new way that I’m going to take forward.”

Third-year student Megan Hippisley likewise recalls needing time to adjust to place-based making.

“It was a shock at first,” she says. “I was used to identifying a problem and then solving it. But now we’re listening to our materials, doing what they want us to do. Which was unexpected, but it’s been an excellent experience.”

Top: For Heather’s class, Megan created a hanging vessel from three salvaged bentwood volumes linked by delicate chains, seen here in a display at the ECU Library. | Bottom: Megan (left) and fellow student Heedo Jang (standing, right) receive guidance on attaching an abalone button to a woven cedar basket from Rita Point Kompst. (Photos by Perrin Grauer)

For Heather’s class, Megan created a hanging vessel from three salvaged bentwood volumes linked by delicate chains. She learned about bentwood from her father, who is Métis with a background in woodworking and a former mill worker. Through their collaboration, Megan became fascinated by the ways material practice can embody cultural and personal histories. She has since become interested in the textile traditions maintained by her mother and grandmother.

Megan adds this interest reflects a broader change in the quality of her curiosity about the world around her. Since taking Heather’s class, she finds herself paying attention to her environment with a newfound interest.

“I’m going outside all the time to find materials or do research, so I get more fresh air, and I’m taking the time to understand how everything around me fits together,” she says. “I listen to my surroundings instead of putting on my headphones and spacing out. I see so many connections. And I feel more connected to home. Making things feels meaningful rather than just making something for its own sake.”

For Heather, Megan and Alex’s experiences represent the development of a vital quality which underpins much of her curriculum.

“I call it resourcefulness,” she says. “And I don’t just mean with regards to materials, but also with regards to questions like, how do I exist in the world? How do I connect with people who know things I don’t know? You don’t have to do everything in life, but that’s a key skill.”